Over 6000 Koreans were slaughtered by the Japanese state and vigilantes following the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. Yet, historiography of the Kanto Massacre often reduces it to an inexplicable historical aberration, or, in more sympathetic accounts, an act of state-sponsored murder. While the latter is undoubtedly accurate, Sunik Kim demonstrates that the massacre only becomes fully comprehensible from a political-economic perspective: that of the Korean worker as relative surplus population, and the Japanese colonial police as direct agent of capitalist production itself.

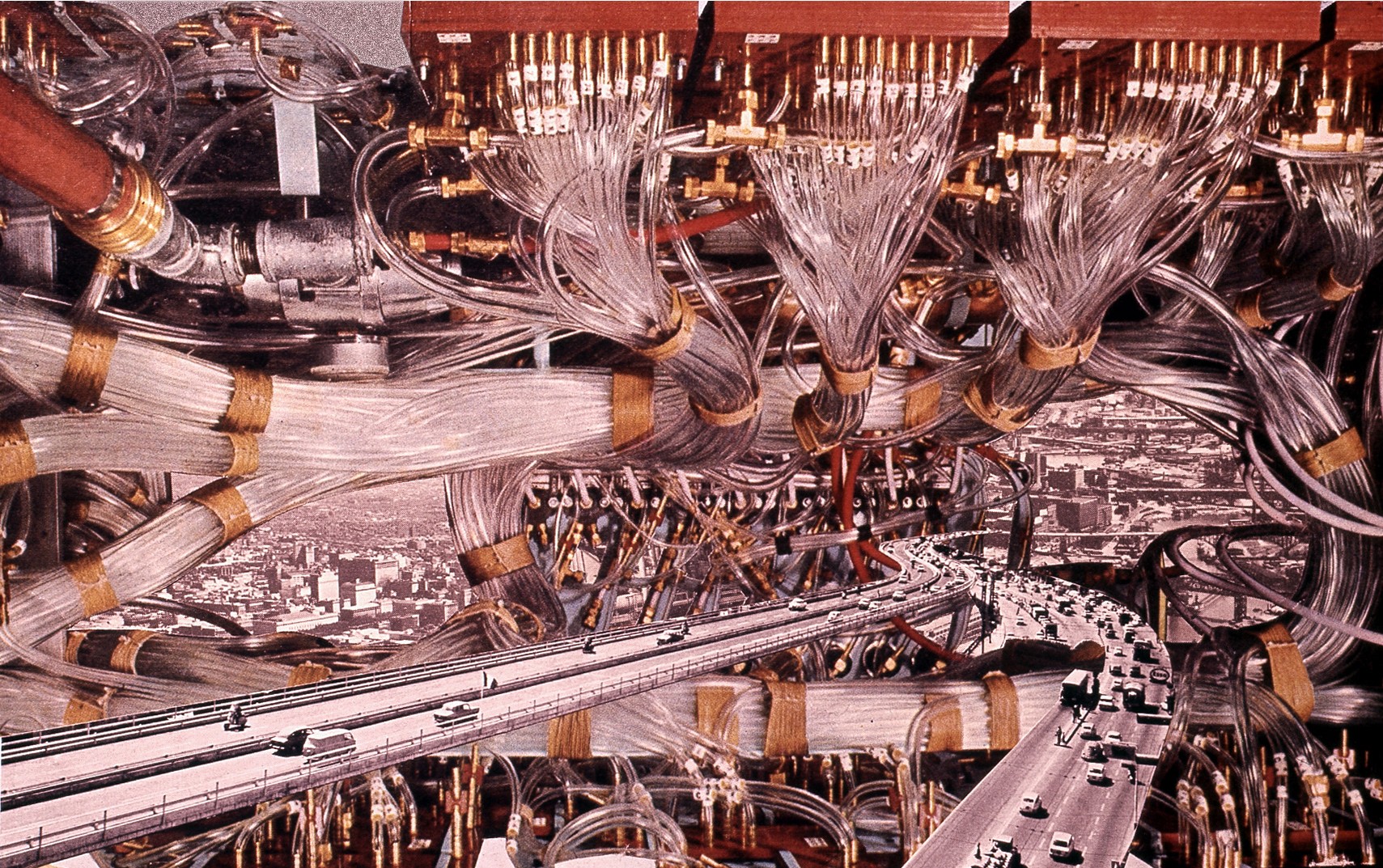

With the recent buy out of Bandcamp as a starting point, finance’s increased presence in the culture industries is analyzed as both a novel phenomenon and an intensification of logics internal to the music commodity. Catalog rights speculation, derivative trading and uneven development in the world-system are all posed as products of finance’s mediating influence. But what does the frontierization of culture entail for independent music?

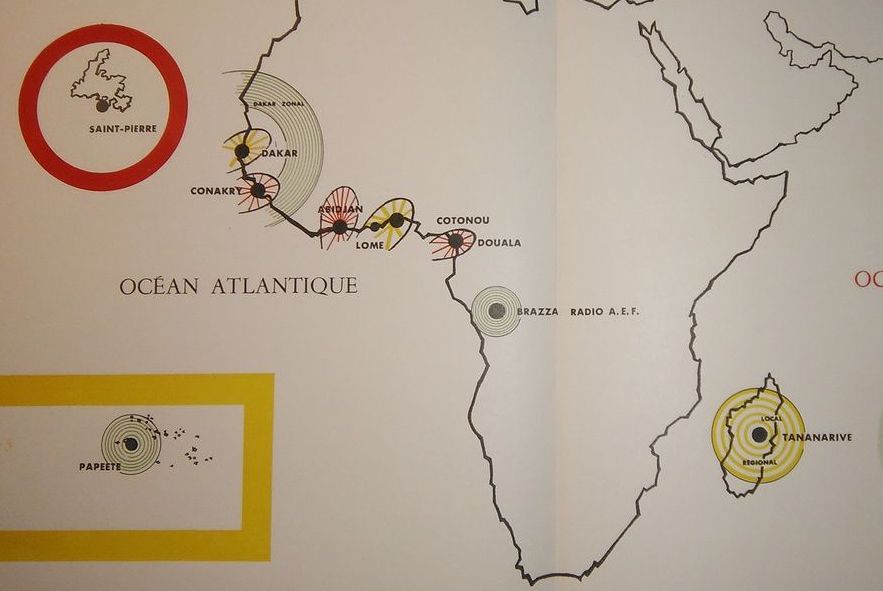

In an essay that interweaves family history with critical theory, Algerian and Indian anti-colonial revolution is analyzed through the lens of Frantz Fanon, the master-slave dialectic and the correspondences between violence, noise and listening. The radio, herein, is both technology of control and vessel for overcoming colonial alienation and domination.

French colonial administration and Pierre Schaeffer’s musique concréte offer a means to untangle the contemporary relationship between sonic autonomy, cultural difference and, on the other hand, syncretism. Towards this end, ethnographic and commercial histories of French colonialism are brought forward into the contemporary corpus of electronic music.

With a practice that is embedded in the cosmologies, political histories and geographies of the Andes – and Aymaran thought in particular – Elysia Crampton enjoins us to consider futures outside the stultifying, death-dealing worlds of coloniality, sounding a music and a sociality that seeks to move beyond the individual towards a form of collectivity that is always in process, a challenge that gets to the heart of Empire’s systemic logics.

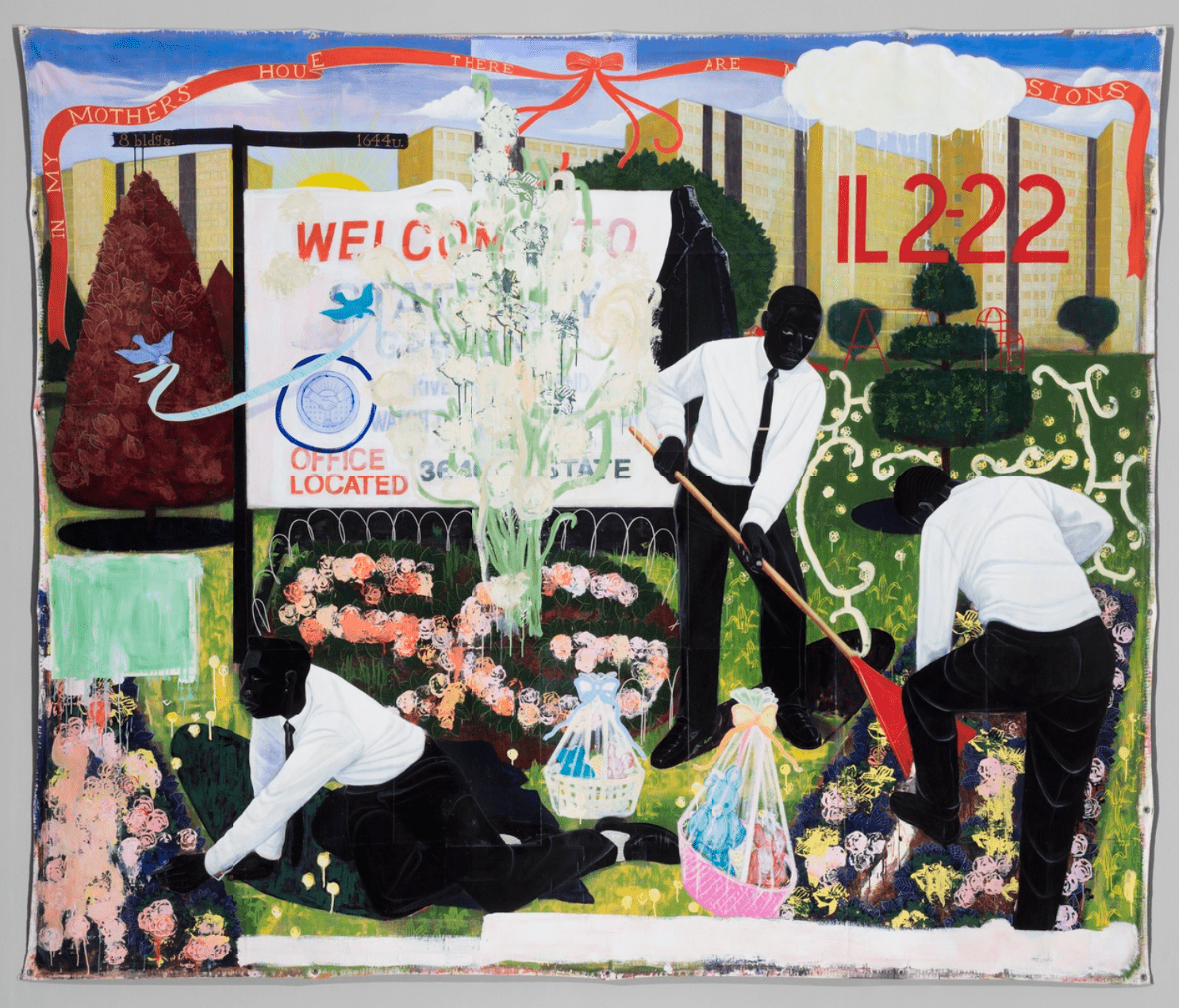

A set of ‘Black Sonic Priorities’ are posed against a landscape pockmarked by racialization, carcerality and incipient fascism. In order to resist regimentation and striation, and move instead towards an aesthetics of excess – the jerk, the stutter and the scream, Authentically Plastic charts a line from the AACM to Hieroglyphic Being in a mapping of the sonic and political present. What, in their words, does the Black body think it is?

An exploration of the tactics, social forms and cultural production of two moments of revolutionary potential in Italy and Chicago. How is culture enmeshed in the creation of anti-capitalist socialities? And what might a conception of autonomy grounded in improvisation and experimentation look like?

Much has been written about the Korean War and the peninsula’s ensuing split into communist North and capitalist South. But what set the stage for the United States’ genocidal war and ongoing occupation? Sunik Kim explores the subtleties of revolutionary action, class composition and diaspora politics in pre-revolutionary Korea.

The tools we use are inherently political, not least the ones we use to produce music. Michael Terren addresses financialization and rentierism in the world of digital audio workstation (DAW) plug-ins. What emerges is a trend towards digital instruments as services, and, in response, the necessity of seizing the means of music production.

The ‘general intellect’ is one of Marx’s most fraught, misunderstood concepts. What accounts for its reemergence in discourses around fully automated luxury communism and blockchain technology? And can the ‘general intellect’ be salvaged from its presumed base in the development of Western capitalist technology?

Bellona Magazine is a biannual journal and publishing collective.

We are a group of artists, culture workers and writers who seek a new paradigm for critical expression. Against the “creative” forms of mass consumption and instrumentalized social relations that predominate in the culture industries today, Bellona is our attempt to resituate criticism as a site of contemplation and contestation. Our primary object of critique is music, specifically its circumscription in the commodity-form, but our interests also range to film, literature and the visual arts, all undergirded by a broad political economic critique. At this conjuncture, it is difficult to imagine a music or a criticism unbound from contemporary exploitation, extraction and subsumption, but Bellona Magazine aims to collectivize the tools currently at hand so as to build towards that future.