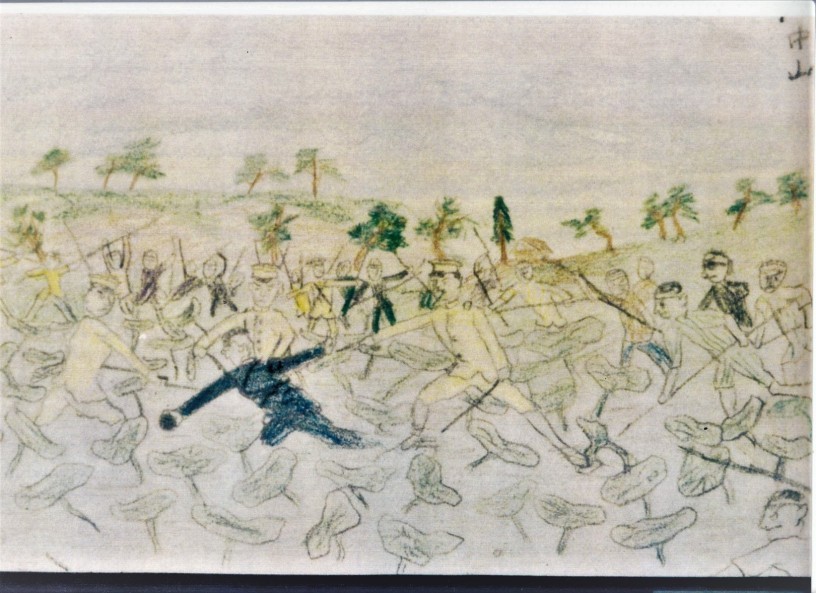

Header Image: Koreans fleeing into a potato field (Iwao Yamazaki, 4th grade at Honyoko Elementary School at the time [of the massacre], preserved at the Tokyo Memorial Hall) [1]

by Sunik Kim[2]

It is virtually impossible to reach any general conclusion as to why select Japanese murdered Koreans following the disaster. Racism, hatred, resentment, and criminal opportunism all contributed to this tragedy.[3]

…the substitution of eclecticism for dialectics is the easiest way of deceiving the people. It gives an illusory satisfaction; it seems to take into account all sides of the process, all trends of development, all the conflicting influences, and so forth, whereas in reality it provides no integral and revolutionary conception of the process of social development at all.[4]

The whole difficulty lies in the fact that the concrete history of the concrete object is not so easy to single out in the ocean of the real facts of empirical history, for it is not the ‘pure history’ of the given concrete object that is given in contemplation and immediate notion but a very complicated mass of interconnected processes of development mutually interacting and altering the forms of their manifestation. The difficulty lies in singling out from the empirically given picture of the total historical process the cardinal points of the development of this particular concrete object, of the given, concrete system of interaction.[5]

The reason is not difficult to explain. Japan was in the throes of a postwar economic crisis…[6]

“Liberation of the colonies!”: this was the cry of migrant Korean workers on May Day 1923 in Yokohama. The rally was organized by Yamaguchi Seiken, a notable labor organizer who had established a union of Korean and Japanese longshoremen in March 1920.[7] The Japanese police responded to the illegal anti-imperialist slogan with ‘exceptionally brutal’ violence; eighteen were arrested, and the police quickly established a new Special Higher Police Division in response to the alarming combination of militant Japanese and Korean workers.[8]

Exactly six months later, on September 1st, 1923, an enormous earthquake erupted on Japan’s Kanto Plain; the quake, and the ensuing tsunamis and firestorms, killed over 100,000 people,[9] rendered 1.38 million homeless, destroyed forty-eight percent of all homes in Tokyo, and leveled 7,000 factories, 162 hospitals, and 117 primary schools.[10] It was, in the words of Korean communist Kim San, “the greatest natural disaster in Japanese history.”[11]

Yamaguchi immediately formed an emergency food relief organization in the wake of the earthquake: “Armed with red flags, Yamaguchi’s men, including a group of Korean workers, gathered May Day-style to feed local residents.”[12] The police and its newly formed Special Higher Police Division saw the food relief efforts—in a neighborhood known as a ‘socialist nest’[13]—as representative of a threatening coalescence of Korean and Japanese workers, the seeds of a potential communist uprising that needed to be stamped out.

They proceeded to do so. In an extended spate of state-led and sponsored murder that has become known as the Kanto Massacre, police, military, vigilantes, and reservists killed Koreans, Chinese migrant workers, and Korean and Japanese communists, socialists, and anarchists en masse; at least 6,000 Koreans were killed in just a matter of days.[14]

In an emergency meeting convened on September 5th at the Police Department of the Emergency Earthquake Relief Bureau, representatives of the military and police censored newspaper articles, falsified death counts, and resolved to prevent Koreans from returning to Korea and spreading news of the massacre: they would report that only five Koreans had been killed in Yokohama.[15] They would also draft a classified memo, “Agreement Concerning the Korean Problem,” in which they would blame the violence, and the rumors that fueled them, on the communist movement, and file charges against 23 Korean suspects.[16] Japanese authorities specifically pinpointed Yamaguchi Seiken as the instigator of the rumors and massacre in Yokohama, and staged show trials of vigilante groups to “convey the image of a law-abiding state punishing its criminals.”[17]

One year later, in commemoration of the earthquake, the government would release the “Taisho era Collection of Heartwarming Stories,” a compendium of tales from the disaster in which ostensible heroes like Tokyo Meguro Mayor Soda Tetsuo protected his six Korean gardener and construction worker employees and later established a refuge for nearly 1,000 Koreans at a horse-track stadium.[18] In reality, Soda’s likely exaggerated story was an extreme rarity: the average Korean worker was more often “handed over to the Divisional Headquarters for questioning” by their capitalist master and “shot to death along the way because they ‘became a threat to the officers’ safety.’”[19] The police even exhumed bodies from the massacre and moved them, preventing families from doing so themselves for fear of revealing the scale of the massacre.[20] Japanese reactionaries continue to deny the massacre to this day.[21]

Such an event inevitably produces many shades of denial. There is, of course, outright denial of the massacre’s existence or scale along the lines of the Japanese state. But, further, on an epistemological level, there is a tempting and ever-present denial of possible explanation: faced with such a horrific aberration, so goes this line of reasoning, we can only hope to speculate as to why this event occurred, and on the appalling scale that it did.

I hope to show that, on the contrary, an explicit rendering of the political economic character of the massacre renders it sensible and, in the most perverse way, logical: the massacre stands as a concrete manifestation of capital’s immanent laws. This character of the massacre—riven with class struggle and contradiction, shaped by the particularities of Japanese capitalism in 1923—is its explanation. In attempting to render the massacre concrete in this way, I hope to pluck the politicized Korean worker and communist from beyond the massacre’s epistemological veil, and in so doing declare in practice that objective reality can be explained and understood as a mediation of the real movement of history, thereby revealing the stakes of this explanation as that of the capacity for historical memory itself.

‘Historical Enigma’

In his Introduction to a Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, Marx outlined a method of ascent from the abstract to the concrete, in which “the concrete concept is concrete because it is a synthesis of many definitions, thus representing the unity of diverse aspects.”[22] As Soviet philosopher Evald Ilyenkov, in his study of Marx’s Capital, elaborates:

This conception of unity in diversity (or concreteness) is not merely different from the one which old logic proceeded from, but is its direct opposite. The conception approaches that of the concept of integrity or wholeness. Marx uses this term in those cases when he has to characterise the object as an integral whole unified in all its diverse manifestations, as an organic system of mutually conditioning phenomena in contradiction to a metaphysical conception of it as a mechanical agglomeration of immutable constituent parts that are linked with each other only externally, more or less accidentally.[23]

It is this latter fragmented, mechanistic epistemology that characterizes much scholarship on the massacre. A survey yields a litany of abstract, endlessly circling statements that perpetually remain on the empirical surface level of the event: “Koreans were the unfortunate victims of a convergence of circumstances that came together in 1923”; [24] “The origins of Japanese attitudes toward Koreans are difficult to discover”; [25] “The earthquake also exposed the darker side of humanity”; [26] “After the 1923 earthquake, racial prejudice mixed with racial fear.”[27] Further, Koreans were apparently killed because of the “prejudice and hostility the Japanese populace had toward Koreans,”[28] and “Prejudice the Japanese had toward Koreans played a role in the Japanese people’s belief of false rumors.”[29] These endless references to ‘prejudice’—to the extent that the Japanese state itself is anthropomorphized and labeled as ‘prejudiced’[30] against the Korean population, as if it were an individual’s opinion rather than an objective form of class oppression, as if the slain Korean worker was merely a victim of ‘prejudice’ as such—actually explain nothing at all: ‘prejudice’ is only the symptom, not the cause, and the cause needs to be uncovered and developed if the investigation is to have any real purpose or explanatory power.

Ultimately, these shrugging platitudes come, intention aside, from the same epistemology as the official language of the Japanese state regarding the massacre, in their structural refusal to offer any explanation of the fundamental causes of the event. The massacre becomes opaque, illegible, a kind of ‘historical enigma’:[31]

In the midst of the confusion of the Great Kantō Earthquake that occurred in September 1923, due to regretful mistakes and groundless rumors, nearly 6,000 Koreans had their precious lives stolen from them. Nearing the fiftieth anniversary of the earthquake, we sincerely commemorate the Korean victims. Understanding the truth of this incident so as not to repeat this unfortunate history, we believe will be the foundation for eradicating racial prejudice, respecting human rights, and forging a road to neighborly friendship and peace.[32]

Others, like Sonia Ryang, argue that the killing of Koreans “fundamentally differed in logic” from the killing of Japanese anarchists and socialists, calling upon Giorgio Agamben’s notion of homo sacer[33] in order to “enormously [deepen] our understanding of the topology and rationale behind the Korean killing of 1923”: [34]

…language, or the tongue became a dividing point to decide who would live and who would be killed. Of course, not all Koreans killed went through the litmus test of ichien gojissen. It is likely that many were killed by neighbors who knew them to be Koreans. Nor were Koreans the only people that were targeted for killing. Japanese anarchists, socialists and other dissidents were also murdered. I shall, however, return to this point with the contention that these were two different types of killing whose fundamental logic differed. I shall say this much at this point: whereas Japanese socialists and anarchists were seen by the authorities as elements that needed to be eliminated, Koreans were seen as killable. [...]

And this leads me to ask; what does it mean, or more precisely, what do we see when some humans are killed as a matter-of-fact, and this killing is not deemed to be murder? And when the tongue—its movement, manipulation, and musculature—is used to distinguish the one-killable from the one-not-killable, how is language positioned in relation to this killing? What is the function of this language?[35]

The tortured and executed Korean worker, and the policeman who committed the act, did not care whether the former was the ‘one-killable’ or the ‘one-not-killable’; this abstract schematization, this vague gesturing at an ‘unlocatable zone,’[36] only obscures the class character of the massacre and erases the politicized Korean worker from history. Here, even in the most sympathetic account of the massacre, we observe the aforementioned epistemological slippage and its stakes: only the Korean-as-such, and the Japanese radical, exist.

Ken Kawashima, in his fantastic work The Proletarian Gamble: Korean Workers in Interwar Japan, pinpoints the same “positivist, empiricist, and sociologizing trap” in the general historiography of Koreans in Japan, identifying it with the Japanese “policeman’s gaze”:

This vast production of knowledge was predominantly statistical, and quintessentially the effect of the policeman’s gaze in Japan. Behind the mountains of statistics and empirical data, however, lay concealed a positivist method that reduced—often by a methodological sleight of hand—various social and economic problems experienced by Koreans in Japan, to a problem of Koreans.[37]

Kawashima argues that the Japanese state would not permit the formation of a politicized Korean proletarian subject and strove to prevent the ‘particular’ Korean struggle from assuming a universal class character.[38] I further contend that bourgeois accounts of the massacre employ an empiricist method that obscures the class character of the massacre, thereby, like the Japanese ‘policeman’s gaze,’ subsuming the politicized Korean proletarian subject into the ‘problem of Koreans’ as such.

Our investigation will reground the massacre in Japan’s colonization of Korea and the intertwined development of Japanese capitalism. It is this political and economic foundation, rather than the mere ‘historical enigma’, that renders the massacre comprehensible—as an expression of the immanent laws of capitalism in all their brutality.

‘Korean Malcontents’

The Kanto Massacre was an extension of state-led political repression of Korean and Japanese communists, socialists and anarchists, and took place in a moment of exceptionally intense and escalating political repression of Koreans.[39]

In the years leading up to the massacre, the Japanese media, in their attempt to “policify the Japanese masses,” repeatedly disseminated alarmist accounts of Korean conspiracies.[40] These narratives “established a discursive style that collapsed the distinction between operational and aspirational plots against the state, resulting in the routine production of stories free from the constraints of reality.”[41] In June 1923, the Tokyo police escalated their repression, arresting over a hundred people for ‘radical activities’ as the newspapers reportedly discovered a plot to overthrow the government and establish communist rule in Japan.[42] The majority were released immediately, lacking any evidence, but those that remained in detention formed a significant proportion of the communist youth in Japan.[43] When the earthquake struck in September, criminal investigation of those communists detained in June was still underway, but the quake turned out to be “an excellent excuse to round up scores of ‘undesirable elements,’ especially socialists, anarchists, Communists, and radical labor leaders.”[44] Further, as many as 1,000 Korean students of all class backgrounds were killed in the massacre.[45]

Kim San, who was a student in Tokyo at the time, observed that after the March First Movement of 1919, “one-third of the students…were poor ‘work-and-study’ students…far more advanced intellectually than the [rich students],” but that ultimately all studied Marxism and 70% of Korean students were communist sympathizers.[46] The March First Movement—a mass, largely nonviolent uprising by the Korean people against Japanese imperialism, brutally repressed by the Japanese military and police—galvanized Korean resistance factions from the peninsula to Manchuria,[47] and raised the specter of a similar rebellion by the colonized in the metropole itself. Accordingly, the police heavily surveilled Korean communities, especially those with suspected communist affiliations.[48]

Immediately following the earthquake, the police posted official public pronouncements[49] that declared it “permissible to kill anyone who appears to be a Korean,”[50] propagated rumors of knife-wielding[51] Korean rapists,[52] and mobilized community vigilante groups that they had helped form one year prior.[53] The police personally ordered men to “arm themselves” and “kill any Koreans who entered the neighborhood.”[54] One sixth-grader recalled that, “The policemen told us that Koreans are coming with knives so we needed to kill them.”[55] Nishizaka Katsuto, head of the Special Higher Police Division and an officer in the colonial police during the March First Movement,[56] stated in a December 1923 internal memo that, following the earthquake, “the police in Yokohama and neighboring regions carried out a ‘grand undercover operation’ with two overlapping goals”; first, “arousing [people’s] fighting spirits,” and second, “preempting subversive actions by ‘delinquent gang members,’” an operation which produced “exceedingly favorable results.”[57]

These ‘delinquents,’ or ‘malcontents’,[58] capable of ‘subversive actions’ were, in Nishizaka’s own words in a 1971 interview, specifically Korean communists:

In short, there was the saying “Korean malcontents” back then. The term referred to communists. I know because I had experience with them in Fukushima. “Korean malcontents” referred to activist Koreans with communist convictions. There were times when I placed the more radical ones under surveillance. As some Koreans in Yokohama had somewhat violent tendencies, someone must have said that “Korean malcontents” were dangerous in such a time of confusion. I think that caused the attacks on Koreans.[59]

The police also mobilized local military reservists—the military itself participated in the massacre[60]—by warning them of incoming bands of armed ‘Korean malcontents.’[61] The reservists, alarmed at the waning public support for the military after World War I, were eager to finally seize the opportunity to “teach the effeminate youth of the peace generation what real war was about” and to counter a culture of “literary indulgence” with a “unique warrior spirit.”[62] Meanwhile, Korean and Japanese anarchists Pak Yeol and Kaneko Fumiko had just one year prior appealed to Japanese workers in the first issue of the magazine Futoi senjin (Bold Korean) that the ‘malcontent Koreans’ simply desire freedom and share the same fate as the Japanese workers.[63] Against invocations of the “ordinary Japanese citizen”[64] spontaneously spurred to horrific acts of racist violence, the majority of vigilantes already acted as an objective wing of the state and representative of the exploiting classes: the leaders of the vigilante groups were landlords and homeowners, and the groups were typically formed via direct prefectural order.[65] Further, other vigilante groups were merely transformed ‘security associations’ that:

had been formed several years before the Great Kantō Earthquake by local strongmen at the town council or municipal level as sub-contracting organizations of the police based on the slogan “turn the police into ordinary people and turn the people into policemen.”[66]

Through this mobilization, the state explicitly prevented Korean workers from communicating and organizing; on September 4th, the mayor of Kamakura stated that “Korean workers are to be…pacified and subjugated…So that they are prevented from organizing, they are to be prohibited from communicating with each other.”[67] The widespread presence of state-approved vigilante groups, police and military simultaneously intimidated and galvanized others[68]: as Jin-hee Lee points out, “[t]o many townsmen, the dispatch of the military and their warning against the potential danger to local communities posed by the rumours seemed not only to verify the credibility of charges against the colonized minorities, but also to condone the killing of alleged ‘rebels’ against their nation.”[69]

Koreans were thus massacred as a politicized ethnic group that, from the perspective of the Japanese repressive apparatus, appeared to pose a genuine existential threat to the Japanese state—though in reality, the communist movement in Japan was at a nascent stage. Not every Korean killed was a communist, but that is completely beside the point; fundamentally, Koreans were killed as communists, with the same logic. In one brutal instance, ten workers and members of the Japanese Communist Party—Kitajima Kichizo, a 19-year-old factory worker who conducted food relief after the earthquake; Hirasawa Keishichi, who helped a Korean family captured by vigilantes; and Kawai Yoshitora, who was caring for three children he had saved from a collapsed house[70]—were stabbed to death at the Kameido police station on September 5th as they sang the ‘Labor Song.’[71]

With this political violence in mind, it is untenable to claim, like Sonia Ryang does, that the massacre was not motivated by “political and ideological conflict.” She argues that even though:

…the political climate in Japan after the Russian Revolution was never stable and the authorities were nervous about any possible solidarity among the oppressed…this still does not explain why ordinary Japanese citizens, hundreds and thousands of them, many of whom were workers themselves, and far from rich, had to kill Koreans on a mass scale. Korean survivors’ accounts also show that they had no idea what trade unions were and many of them hardly understood the Japanese language, let alone working-class solidarity.[72]

Ryang remains on the quantitative surface level of the event: because x Koreans / y total Koreans did not know what trade unions were, and x number of “ordinary Japanese citizens,” an apparently neutral monolith bearing no class divisions or ideologies, participated in the massacre, the massacre was not politically or ideologically motivated. Here Ryang conflates the actual strength of the working-class movement in 1923—which was still very low, but growing—with the perception of that strength, and its potential for growth, by the state and its agents—many of whom were ‘ordinary citizens’—in order to outright dismiss the fact that the massacre was politically motivated (she calls the ‘political’ explanation ‘more unwarranted’ than an ‘economic’ explanation).[73] The class struggle—which necessarily involves political and ideological struggle—is reduced to the level of quantifiable data and easily set aside. In reality, the class struggle in its concreteness necessarily modulates, and is modulated by, an immense complexity of historical forms including Ryang’s language test. Denial of the operative role of class struggle in the historiography of the massacre inevitably erases the politicized Korean worker from history.

The ‘Korean Problem’

Lenin, in an attempt to “expose the plunder of the [Russian] state” in the spring of 1917, stated:

When capitalists work for defence, i.e., for the state, it is obviously no longer “pure” capitalism but a special form of national economy. Pure capitalism means commodity production. And commodity production means work for an unknown and free market. But the capitalist “working” for defence does not “work” for the market at all—he works on government orders, very often with money loaned by the state.[74]

Lenin emphasized that there are no ‘pure’ phenomena in nature or society, that there never was or can be a ‘pure’ capitalism, that “what we always find is admixtures either of feudalism, philistinism, or of something else”—and that “dialectics shows that the very concept of purity indicates a certain narrowness, a one-sidedness of human cognition, which cannot embrace an object in all its totality and complexity.”[75] Accordingly, Japanese capitalism, like all capitalisms, bore certain concrete—and inextricable—peculiarities: the outsized importance of monopoly cartels that acted as executors, extensions, of government national and foreign policy; and, as we will see through Kawashima’s analysis, the ‘problem’ of a Korean relative surplus population stemming from Japan’s colonial domination of the peninsula—a phenomenon facilitated by transformations in the logic of Japanese capital. The Kanto Massacre stands as an organic and logical manifestation of this concrete Japanese capitalism with all its political and economic contingencies, triggered, but not explained, by the unforeseen singularity of the earthquake and its devastation.

From the Meiji Restoration of 1868 to the end of the 1880s, the Japanese economy shifted from a feudalism based on petty industry—developed by the Shogunate and a samurai class undergoing rapid disenfranchisement—to a capitalism fueled by tradesmen, or ‘Meiji men,’ who privatized industry and, in collaboration with the Japanese state, formed powerful financial cliques called zaibatsu that accelerated the concentration and accumulation of Japanese capital.[76] The zaibatsu was explicitly modeled on the Western monopoly cartel but attempted to dominate not just a single industry but rather a diversity of enterprises.[77] A wealth of capital was available to these zaibatsu due to a context of almost limitless demand for—and cheap supply of—labor and raw materials[78] fueled by ongoing Japanese territorial expansion: an arrangement of mutual benefit between the state and the cartels that rendered the two inextricable. The zaibatsu played a key role in Japan’s expansionist and annexationist aspirations,[79] with the Japanese state awarding them lucrative contracts to support its colonial ventures.[80] The zaibatsu were essentially ‘undertakers’ of state policy, whose primary funding came from the government itself.[81] Of course, amidst this rapid capital accumulation, the working class and large swathes of the peasantry remained destitute.[82]

During World War I, Japanese industry underwent an enormous war-fueled boom; Japan transformed from being a debtor of 1.1 billion yen in 1914 to a creditor of 2.77 billion yen in early 1920.[83] Accordingly, factories multiplied across the country, increasing from 31,717 in 1914 to 45,806 in 1920, with the number of factory workers rising in the same period from 948,000 to 1,612,000.[84] While nominal wages rose, they did not keep up with prices of consumer commodities, leading to strikes in which workers demanded higher wages: Kawashima details how, “[i]n 1914, there were 50 strikes involving 7,904 workers; in 1919, the number of strikes increased ten-fold to 497, involving 63,137 workers.”[85]

Faced with an increasingly organized and militant working class, “Japanese industry looked to Korea for fresh blood.”[86] This process entailed Japanese capitalists recruiting Korean peasants from the peninsula as “cheap, temporary, and non-unionized industrial workers,” contracted for short-term work in factories and coal mines.[87] At the peak of recruitment in 1917, 28,737 Korean workers were brought to Japan via 80 recruitment outings.[88]

The Korean workers, largely peasants, had been expropriated from their land by the Japanese state in order to artificially increase rice production in Korea.[89] In the years following the formal annexation of Korea in 1910, the Japanese colonial government, in collaboration with Korean landed aristocracy, reformed the land tax system, turning it into a cash funnel for the colonial government.[90] Though taxes were kept artificially low to promote colonial investments, the vast majority of Korean peasants struggled to make these increasingly exorbitant payments, and many were driven into bankruptcy.[91] Peasants were forced to relinquish ownership of their land and work for landlords to survive—especially after the rice production drive began in 1920. In this economic context, Korean village units began to disintegrate, and peasants underwent the processes characteristic of primitive accumulation: having been divorced from their means of production, the Korean peasant was proletarianized and forced to rely upon wage-labor for survival.

As Marx demonstrates in his discussion of primitive accumulation, a section of the proletariat are produced as a relative surplus population, or industrial reserve army: a population of workers are made unnecessary for capital’s self-valorization and are thus unable to find work. They are rendered unemployed paupers living on the fringes of society—ready to be thrown en masse back into the workforce whenever capital suddenly expands into an existing or new branch of industry.[92] Korean workers, accordingly, were “not hired as regular workers but rather as temporary and supplementary workers whose employment was only intended to meet a brief labor shortage stemming from the war-time manufacturing boom,”[93] which ended between 1918 and 1920.[94]

The recruitment process was directly administered by Japanese colonial police,[95] and police involvement was an absolute, not coincidental, condition for recruitment:[96] they oversaw the entire recruitment application process, and police in Korea reported on the workers in the peninsula for the benefit of police in Tokyo and Osaka.[97] They would also directly set wages for the Korean workers by providing guidelines to the Japanese companies seeking cheap Korean labor,[98] establishing a tiered wage system based on ethnicity. The cheapness of Korean labor was an obvious boon to the Japanese capitalists, not only allowing for reduced production costs but also exerting a downward pressure on wages for the rest of the working class in Japan. As Kawashima observes, a Japanese newspaper reported in 1917 that “[t]he importation of Korean workers to Japan holds great promise for capitalists insofar as they reduce production costs and increase profits; moreover, unlike Japanese workers, they are not unionized.”[99] The Japanese police concurred, stating: “Because Korean workers do not fiercely confront their bosses with the same tenacity of purpose as Japanese workers, Korean workers have been employed experimentally as a supplementary work force.”[100]

After the brief manufacturing boom fueled by World War I ended between 1918 and 1920, many workers were subsequently thrown into the streets. Accordingly, in the words of the Japanese police to steel factory recruiters in Osaka: “With the end of the war and the increasing problem of excess workers, the hiring of Koreans will no longer be to the employers’ advantage.”[101] Korean workers, already pauperized due to their artificially lowered wages and unstable employment, in the words of the Japanese police, “stranded in Japan, have fallen into a life of poverty, thereby becoming a serious burden on the police.”[102]

Given the economic downturn and the increasing inability to find work, Korean workers began to demand compensation and repatriation, leading to militant actions like those of the Yubari Coal Mine workers on March 26, 1918, in which 150 recently recruited Korean workers rebelled against the police in a ‘bloody showdown’ after seeing, in the company hospital, all the workers killed and maimed in the mines.[103] The Koreans injured in the rebellion were taken directly to the police, not the hospital, proving, as Kawashima argues, “the extent to which the police were fundamentally part of the entire recruitment process…to the very process of production itself in Japan.”[104] Further proving this point, police played an integral role in the housing conditions of the Korean workers: Korean workers were separated from Japanese workers and constantly surveilled, and disruptions in recruiting—integral to the Japanese capitalist system in 1923—led to increased policing of already recruited workers in all aspects of their daily lives.[105]

The March First Movement of 1919, in conjunction with the economic downturn and the militancy of Korean workers—itself a response to increasing unemployment and abuse in the workplace—led to the creation of a passport system wherein only those Koreans who were going to Japan to work were permitted to travel—“not as activists, but as laborers.”[106] In this nexus of upheaval and repression, Koreans began to form political organizations in Japan: anarchist Pak Yeol founded the Black Wave Association and Black Friends Association from 1921-1922, which “promoted class struggle and direct action as vehicles for national independence,” and the communist Northern Star Association, Tokyo Korean Labor Federation, and Osaka Korean Labor Federation were formed in 1922, the latter of whose mission statement read:

Our mission is to triumph in class struggles, to establish basic rights of survival of the working class…And in toppling the capitalist system that exploits us to the bone, we will strive to establish a new society on the basis of workers.[107]

The Japanese state and police now had reason to suspect any of these recruited and, increasingly, unemployed Korean workers as strong candidates for participation in anarchist, socialist and communist movements: the Korean workers in Japan had become what Kawashima calls an “uncontrollable colonial surplus,” one that would persist through the economic downturn of the 1920s and early 1930s.[108]

Despite dwindling opportunities for work, deteriorating working conditions, and intensifying economic and political repression, Koreans continued to flood to Japan because of worsening rural conditions in 1920s and 1930s Korea.[109] Ultimately, this “Korean problem,” as Kawashima argues, “not only intensified but morphed into different shapes and forms that frustrated, baffled, and exasperated Japanese police, factory and public works construction bosses, welfare organizations, unemployment bureaus, and urban Japanese landlords.”[110]Japan’s colonization of Korea had, with the “inexorability of a natural process,”[111] reacted back upon the Japanese ruling class in the form of a group of surplus workers who could not be absorbed into the capitalist state’s political or economic structures and thereby became increasingly subjectively and objectively antagonistic to that state.

The Korean Worker: “A Precious Gem Indeed”

With this grounding in the economic, it becomes clear that the earthquake—which was the immediate trigger, but not the fundamental cause, of the massacre—struck at a brief, concrete historical nexus wherein: (1) Korean workers had become a politicized surplus working population that, in that moment, served little productive purpose to capital; (2) The organization and militancy of the proletariat in Japan had just begun to grow to a point that actively concerned, and united, the Japanese ruling class, but the working-class movement remained embryonic and largely unable to defend itself; and (3) The police played a directly economic function as personification of capital and direct agent of capitalist production itself, specifically in relation to the Korean worker, rather than a mere representative or enforcer of the capitalist state.

These factors and their interrelation not only explain why the massacre occurred, but also the appalling scale at which it occurred. During the massacre itself, that very same police fabricated and disseminated pronouncements about ‘malcontent’ Koreans, and directly instigated and participated in the killing; as personifications of capital, they were already primed—not merely subjectively and psychologically, but objectively, through the repeated practice of hiring, surveilling, ‘housing’, managing, disciplining, imprisoning, and killing Korean workers in the years leading up to 1923—to treat the Korean worker as unproductive, politically threatening refuse that needed to be forcibly eliminated from society.

Per the Japanese state in December 1922:

As a result of the economic recession in Japan, not only have countless Koreans become roving vagabonds with no work; they are increasingly involved with social and labor movements in Japan, and are carrying out mass actions and demonstrations…After conferring with the Sotokufu, it has been agreed that free travel and group recruitments should be aggressively reduced.[112]

Further, observe the rhetoric of Pak Ch’um-gum, Korean leader of the Soaikai—a Korean-managed, state-funded “welfare organization specializing in Korean workers”[113] that had an effective “monopoly over Korean day labor in Tokyo”[114]—in 1923, regarding the surplus Korean worker:

Korean workers have wandered into every region of Japan, and their thought has strayed into evil ways. It pains us to think of how they take part in spontaneous acts of violence, curse the Japanese state [literally, to cast a spell over the state], hold grudges against others, plot various crimes…and hinder the spirit of the annexation between Japan and Korea. That all Koreans are mistakenly considered lazy is the fault of the Korean gorotsuki. These thugs, vagabonds and punks…drag down the innocent and pure Koreans, and are known for organizing political groups which threaten factory bosses and foremen. So for the sake of Japanese–Korean relations, they simply must be eradicated and driven out of Japan. If we find any of them, we’ll investigate their personal histories, check any criminal records they might have, and give them stern advice. For those who show a resilience to repent, we will contact the government-general or the Pusan police bureau [in Korea] and move to expel these punks and thugs from Japan once and for all.[115]

As the Korean worker, “briefly considered indispensable as a supplementary labor force,” quickly became an unproductive surplus population during the recession, they also became the first target for layoffs.[116] Marx demonstrates that to be displaced and pauperized, far from being a merely ‘temporary inconvenience’ for the worker, means ‘chronic misery’ and death by starvation; he calls the ‘gradual extinction’ of the English hand-loom weaver displaced by machinery one of the most frightful spectacles in world history.[117] Further, Marx emphasizes that when the transition towards displacement occurs ‘in degrees’, the result is chronic misery; but “when the transition is rapid, the effect is acute and is felt by great masses of people,” as seen when the English colonial government introduced cotton machinery in India: “The Governor General reported as follows in 1834-5: ‘The misery hardly finds a parallel in the history of commerce. The bones of the cotton-weavers are bleaching the plains of India.’”[118]

The Kanto Massacre was the result of this rapid transition of the Korean worker from indispensable to surplus. It performed the very same culling function as what Engels called social murder in the politically short-circuited form of direct murder, itself heightened as if in a hothouse by the tremendous scale of the earthquake’s devastation and the state’s attendant drive towards self-preservation against the “threat of organized dissent by malcontented Koreans.”[119]

At a certain point, however, just as the capitalist cannot kill off all of their unruly workers to perpetuity, not every Korean in Japan could be killed, because a certain quantity of their labor-power was still required to reproduce the Japanese capitalist system. Witness the Prime Minister’s appeal to the Japanese nation on September 5th:

That the public themselves should take measures to persecute and threaten Koreans, is not only inconsistent with the (policy) principle of Japan-Korea assimilation but such practices, if reported overseas will certainly produce undesirable effects…I sincerely hope that the nation will seriously reflect on the matter and maintain an attitude of self-respect.[120]

This ‘Japan-Korea assimilation’ primarily meant the successful importation and assimilation of Korean workers into the Japanese capitalist system: in 1917, the peak of recruitment of Korean workers, “[n]ewspapers glowingly reported that the importation of Korean labour signified the early success of Japan's assimilation policy in Korea, and the 12 August 1917 edition of the Fukuoka Nichi Nichi, for example, commented that the use of Korean labour not only compensated for the wartime labour shortage but released Japanese workers for more sophisticated types of work.”[121]

Immediately after the earthquake, the police and army called upon the Soaikai to “prevent Koreans from fleeing the burning city by forcibly housing them in newly constructed Soaikai worker dormitories and barracks.”[122] Maruyama Tsurukichi, the chief of the Tokyo police department, then ordered the Soaikai to transform the dorms into a ‘shuyujo’—a term encompassing home, camp, asylum, and prison—to both ‘protect’ Koreans from further massacres and prevent them from escaping and spreading news of the massacre.[123] These Korean workers were immediately recruited by the department of civil engineering, the police, and the army, to reconstruct the burnt-out city.[124] The Korean-led Soakai supervised the Japanese army’s mobilization of 4,000 Korean workers in the reconstruction of Tokyo, and also organized groups of Korean workers to work in construction with pay.[125] Upon the completion of this labor, Pak Ch’um-g’um would state:

Before the earthquake, Japanese wouldn’t use the workers [the Soaikai] sent to construction sites…But now that they’re finally being used, feelings between Japanese and Koreans have become much more harmonious…Little interest was given to Korean workers before, but now employers have taken considerable interest in them. Employers have opened their eyes, and this is a wonderful thing.[126]

With this ‘success’, the Soakai became an official sub-contractor of the Tokyo government, and were handed some of the city’s largest contracts; by 1924, investments from private corporations and the military “poured into Soaikai coffers.”[127] The surplus population of Korean workers in Japan, artificially whittled down by the massacre, now temporarily conformed to the needs of capital’s self-valorization, even more so as construction became a centrally important branch of industry in the wake of the earthquake’s destruction. The surviving Korean workers were, for now, seen by capital as productive once again, and were thereby reincluded in capital’s circuit of production and reproduction, granting them an economically contingent semblance of safety from state-sanctioned mass murder. Witness statements from Japanese capitalists and labor bureaus demonstrate this point:

Due to the boom in state-led urban planning projects, an acute labor shortage has been felt in the public works labor market, especially in the fall season…Korean workers are hired en masse, especially in times when a sudden demand for labor power is made. In this regard, Korean construction workers are a precious gem indeed.[128]

Korean construction workers are…a precious labor force.[129]

Further, as Kenji Hasegawa points out, the appearance of ‘Korean malcontents’ in the Japanese mass media peaked between the March First Movement of 1919 and the earthquake, then declined after the post-massacre media campaign scapegoating ‘Korean malcontents’ and Yamaguchi Seiken.[130]

“Revive that blood, flowing with bitterness”

Marx is careful to present the capitalist as “capital personified and endowed with consciousness and a will,”[131] whose “soul is the soul of capital”[132]:

To prevent possible misunderstanding, a word. I paint the capitalist and the landlord in no sense couleur de rose [i.e., seen through rose-tinted glasses]. But here individuals are dealt with only in so far as they are the personifications of economic categories, embodiments of particular class-relations and class-interests. My standpoint, from which the evolution of the economic formation of society is viewed as a process of natural history, can less than any other make the individual responsible for relations whose creature he socially remains, however much he may subjectively raise himself above them.[133]

From the perspective of the totality of society under the capitalist mode of production, Marx elaborates, “what appears in the miser as the mania of an individual is in the capitalist the effect of a social mechanism in which he is merely a cog…competition subordinates every individual capitalist to the immanent laws of capitalist production, as external and coercive laws.”[134] The Kanto Massacre stands as a manifestation of these immanent laws in the particular conjuncture of 1923 Japan. There were undoubtedly “grand undercover operations” planned and conceived in backrooms by the Japanese ruling class during the massacre and its aftermath. However, my point is not to prove that there was a single, insidious conspiracy behind the proceedings; rather, it is simply that the objective structure of the Japanese economy in 1923, and the political forms and class relations that both emerged from and reacted back upon that structure, ultimately determined, and explain, the horrific course of events in September 1923. Lacking this foundation, the massacre remains inexplicable, a mere ‘historical enigma’.

With this context in mind, Sonia Ryang’s dismissal of an ‘economic’ explanation for the massacre becomes untenable: her argument rests upon the fact that there were only 20,000 Koreans in Tokyo and Kanagawa prefecture at the time, which, demographically, is hardly “a number that would threaten job availabilities for [the] native working class. Considering that Japan’s industry was being rapidly modernized, the existence of less-than-minimum-waged Korean workers in the fringe job line could not have posed a serious threat.”[135] By empirically reducing the ‘economic’ explanation to a mere quantitative proportion between two groups of workers, Ryang dismisses the objective role of Japanese capitalism itself in the massacre, stretching all the way back to its colonization of the peninsula, its expropriation of the Korean peasant, and the attendant formation of a surplus Korean worker. The outcome, once again, is to erase the politicized Korean worker from history and absolve the capitalist mode of production of its fundamental role in the massacre. To this point, Ryang goes on to ask:

...why is the 1923 earthquake the only incident that brought about all-round Korean hunt and killing, committed by Japanese civilians, throughout the history of colonial relations between Japan and Korea (1910-1945)? … why were Koreans not persecuted on a mass scale during wartime, especially upon noticeable encroachment by the Allied Forces? … This is because the reason of the 1923 killing is to be found not simply in colonial relations, but in a somewhat more fundamental place.”[136]

Here we see the danger of the empiricist approach on full display. Because Ryang divorces the massacre from its economic and political foundation, she accordingly places the economic and political oppression of Koreans in a different logical category than the massacre itself. The end result is a papering over of that economic and political oppression, to the point that Koreans in Japan are framed as not being persecuted on a mass scale during World War II.

As Kawashima noted, the World War I-fueled economic boom ended around 1920, and the earthquake and massacre occurred just as the ‘Korean problem’ of excess, unproductive and politically threatening workers was permeating all aspects of Japanese society and troubling the ruling class. Further, the working-class movement in Japan continued to strengthen through the 1920s: Roso, the largest Korean communist labor union in Japan, was established in 1925, and played a significant role in the Sanshin Railway strike of 1930, described by Pak Kyung-sik as “absolutely epoch-making and revolutionary”:

It was the first strike in Japan to be led by a Korean strike committee. It was the first strike to have a significant influence across Aichi prefecture and on the Japanese workers in Okazaki City in particular. [Korean] strikers at Sanshin received massive support from the peasants of the region. In turn, Sanshin sparked new beginnings of the peasant movement in the region. Thus, in many important ways, Sanshin heralded a series of new political initiatives and beginnings. Following Sanshin, comrades in all regions were able to gather courage to develop and extend their own struggles.[137]

In 1931, Japan invaded Manchuria, beginning its new wave of imperialist expansion that would culminate in World War II: these annexations, by intention, opened up vast new territories and markets where industry could be established and workers employed. In this context, Koreans were no longer a purely unproductive surplus, but once again necessary for the needs of Japanese capital’s self-valorization and expanded reproduction. Accordingly:

Wartime labor shortages led to enforced migration. In the name of eliciting ‘volunteers,’ ethnic Japanese and Koreans colluded in the conscription of Koreans to work in factories and mines. Between 1939 and 1945, 700,000-800,000 Koreans were made to work in Japan…Beginning in 1944, 110,000 ethnic Koreans were conscripted by the Japanese military. Many Koreans in Japan suffered war-related injuries and deaths: 239,320 Koreans…Up to 30,000 ethnic Koreans died in the atomic bomb explosion in Hiroshima.[138]

Were these hundreds of thousands of Koreans not persecuted on a mass scale during wartime?

My point is not to directly equate mass murder with the often indirect murder of capitalism and imperialism; rather, I stress that the Kanto Massacre was an extreme but direct extension of the latter, and that the particularly gruesome violence involved is a perfectly normal course of events under an imperialist regime that must necessarily be linked to and traced from the capitalist world-system’s internal laws. The direct involvement of the police in the process of production also demonstrates how capitalist accumulation in its concreteness blurs the distinctions between ‘direct’ and ‘indirect,’ and ‘political’ and ‘economic’ violence. As just one example, the Bodo League massacre, which is widely understood as an anti-communist killing, followed the same fundamental logic as the Kanto Massacre. In 1949, hundreds of thousands of Koreans, many of whom “had nothing to do with the left-wing,” were rounded up by the South Korean government en masse as suspected leftist sympathizers and enrolled in a ‘re-education’ movement called the National Bodo League, under “the pretext of protecting them from execution.”[139] Beginning in 1950, as the war progressed, anywhere from 60,000 to 200,000 of these suspected leftists were massacred by police, military and anti-communist paramilitary groups led by collaborators of the Japanese colonists,[140] for fear that they “might side with the enemy.”[141] The South Korean government has suppressed evidence of the massacre for decades. How different is this from the state-led mass killing of ‘Korean malcontents’ who were perceived as a threat to the Japanese state in 1923?

In attempting to identify a concrete cause of the massacre, I hope to demonstrate that the stakes of such an identification, the stakes of such a preliminary tracing of the intertwining and colliding of economic, political, social, and historical forces, reverberate far beyond this particular domain. At risk of hyperbole, what is at stake is historical memory itself. A grounded analysis of events not only resuscitates the politicized Korean worker and communist, who died fighting for total liberation, from the necropolis of empiricist scholarship and outright denialism; it is also a declaration-in-practice that objective reality can be explained, that reality, which necessarily includes our own history, bears its own laws and trajectories that can be understood just like any other really-existing organism. Faced with staggering and horrifying atrocities—as I complete this essay in July 2024, two years after beginning, Israel has just slaughtered over 81 Palestinians in Khan Younis[142]—we must remain steadfast, fixated on the totality and all its complexities, so that we may better revolutionize that totality. I will end on two quotations, one from Marx, and one from Zainichi proletarian poet Kim Yong-je’s “Memories of the Earthquake,” published in Women’s Battle Flag (fujin senki), 1931:

The essence of bourgeois society consists precisely in this, that a priori there is no conscious social regulation of production. The rational and naturally necessary asserts itself only as a blindly working average. And then the vulgar economist thinks he has made a great discovery when, as against the revelation of the inner interconnection, he proudly claims that in appearance things look different. In fact, he boasts that he holds fast to appearance, and takes it for the ultimate. Why, then, have any science at all?

But the matter has also another background. Once the interconnection is grasped, all theoretical belief in the permanent necessity of existing conditions collapses before their collapse in practice. Here, therefore, it is absolutely in the interest of the ruling classes to perpetuate a senseless confusion.[143]

***

Think of that brutal memory of fresh blood

And connect it to your lives of today

Revive that blood, flowing with bitterness

On the path of the proletarian battle procession[144]

Notes

-

“Koreans fleeing into a potato field (Iwao Yamazaki, 4th grade at Honyoko Elementary School at the time [of the massacre], preserved at the Tokyo Memorial Hall)” ↑

-

“Proletariat of a cursed colony” is a line from Zainichi proletarian poet Kim Yong-je’s 1931 poem “The Night Before: From Your Korean Comrades” (Nikki Dejan Floyd, ‘Bridging the Colonial Divide: Japanese-Korean Solidarity in the International Proletarian Literature Movement,’ Yale University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses (2011), p. 267) ↑

-

J. Charles Schencking, ‘The Aftermath - The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923’ <http://www.greatkantoearthquake.com/aftermath.html> ↑

-

V.I. Lenin, ‘The State and Revolution’ (1917) <https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/staterev/ch01.htm> ↑

-

Evald Ilyenkov, ‘The Dialectics of the Abstract and the Concrete in Marx’s Capital’ (1960) <https://www.marxists.org/archive/ilyenkov/works/abstract/abstra4.htm#4c01> ↑

-

Kim San and Nym Wales, Song of Ariran: A Korean Communist in the Chinese Revolution (San Francisco: Ramparts Press, 1972), pp. 36 ↑

-

Kenji Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ Monumenta Nipponica, 75.1 (2020), pp. 107-108 ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ pp. 107-108 ↑

-

Tessa Morris-Suzuki, ‘Un-remembering the Massacre: How Japan’s “History Wars” are Challenging Research Integrity Domestically and Abroad,’ Georgetown Journal of International Affairs (2021) <https://gjia.georgetown.edu/2021/10/25/un-remembering-the-massacre-how-japans-history-wars-are-challenging-research-integrity-domestically-and-abroad/> ↑

-

Schencking ↑

-

Kim and Wales, p. 36 ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ p. 108 ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ p. 108 ↑

-

Kim and Wales, p. 36 ↑

-

Mai Denawa, ‘Behind the Accounts of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ Brown University Library Center for Digital Scholarship (2005) <https://library.brown.edu/cds/kanto/denewa.html> ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ p. 94 ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ p. 94 ↑

-

Denawa ↑

-

Denawa. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

Shoji Yamada, ‘What happened in the area of Greater Tokyo right after the Great Kanto Earthquake?: The State, the Media and the People,’ Comparative Genocide Studies, 3 (2012/2013), p. 21 ↑

-

Morris-Suzuki ↑

-

Karl Marx, ‘Introduction to a Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy’ (1859) <https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1859/critique-pol-economy/appx1.htm> ↑

-

Evald Ilyenkov, ‘The Dialectics of the Abstract and the Concrete in Marx’s Capital’ (1960) <https://www.marxists.org/archive/ilyenkov/works/abstract/abstra1c.htm>. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

J. Michael Allen, ‘The Price of Identity: The 1923 Kanto Earthquake and Its Aftermath,’ Korean Studies, 20 (1996), p. 85 ↑

-

Allen, p. 78 ↑

-

Joshua Hammer, ‘The Great Japan Earthquake of 1923,’ Smithsonian Magazine, 2011 <https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-great-japan-earthquake-of-1923-1764539/> ↑

-

John Lie, Zainichi (Koreans in Japan): Diasporic Nationalism and Postcolonial Identity (University of California Press, 2008), p. 5 ↑

-

Denawa ↑

-

Denawa ↑

-

Denawa ↑

-

Jinhee Lee, ‘The Enemy Within: Earthquake, Rumors, and Massacre in the Japanese Empire,’ Faculty Research & Creative Activity, 58 (2008), p. 187 <https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/154556601.pdf> ↑

-

Gennifer Weisenfeld, Imaging Disaster: Tokyo and the Visual Culture of Japan’s Great Earthquake of 1923 (University of California Press, 2012), p. 306 ↑

-

In 2020, Agamben utilized this conceptual framework to deny the existence of the COVID-19 pandemic: https://slate.com/human-interest/2022/02/giorgio-agamben-covid-holocaust-comparison-right-wing-protest.html ↑

-

Sonia Ryang, ‘The Tongue That Divided Life And Death: The 1923 Tokyo Earthquake and the Massacre of Koreans,’ Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 5.9 (2007) <https://apjjf.org/Sonia-Ryang/2513/article> ↑

-

Ryang, ‘The Tongue That Divided Life And Death: The 1923 Tokyo Earthquake and the Massacre of Koreans’. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

Ryang, ‘The Tongue That Divided Life And Death: The 1923 Tokyo Earthquake and the Massacre of Koreans’ ↑

-

Ken Kawashima, The Proletarian Gamble: Korean Workers in Interwar Japan (Duke University Press, 2009), pp. 19-20 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 22 ↑

-

“In the spring of 1923, Japanese authorities’ vigilance toward, and repression of, Koreans was at its peak…On May Day that year (May 1st) the police agency banned socialists and other ideological groups from participating in celebrations. The ideological groups that received particular attention were the Korean.” Yamada, pp. 6-7 ↑

-

Kenji Hasegawa, ‘The 8 P.M. Battle Cary: The 1923 Earthquake and the Korean Sawagi in Central Tokyo,’ Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 20.12.4 (2022) <https://apjjf.org/2022/12/Hasegawa> ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The 8 P.M. Battle Cary: The 1923 Earthquake and the Korean Sawagi in Central Tokyo’. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

Rodger Swearingen and Paul Langer, Red Flag in Japan: International Communism in Action 1919-1951 (Harvard University Press, 1952), p. 19 ↑

-

Swearingen and Langer, p. 19 ↑

-

Swearingen and Langer, p. 19 ↑

-

Kim and Wales, p. 36 ↑

-

Kim and Wales, pp. 34-35 ↑

-

See my ‘Joseon Bolshevik,’ Bellona Magazine (2022) <https://bellonamag.com/joseon-bolshevik> ↑

-

Yamada, p. 6 ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ p. 94 ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ p. 98 ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ p. 98 ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ p. 111 ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ p. 99 ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ p. 99 ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ p. 94 ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ p. 94 ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ p. 94. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ p. 101 ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ p. 104. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

Yamada, p. 14 ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ p. 101 ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ p. 112 ↑

-

Yamada, p. 8 ↑

-

Ryang, ‘The Great Kanto Earthquake and the Massacre of Koreans in 1923: Notes on Japan’s Modern National Sovereignty,’ p. 738. ↑

-

Yamada, p. 13 ↑

-

Yamada, p. 13. This drive to “policify the masses” stemmed from a meeting between Japanese police and the New York Police Department in 1917. See Kawashima, pp. 135-137. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ p. 106. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

Yamada, p. 10 ↑

-

Lee, p. 196. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

‘Hidden history behind 1923 quake: communists killed by power,’ Japan Press Weekly, 2013 <https://www.japan-press.co.jp/modules/news/?id=6439> ↑

-

Michael Weiner, ‘Koreans in the aftermath of the Kanto earthquake of 1923,’ Immigrants & Minorities: Historical Studies in Ethnicity, Migration and Diaspora, 2.1 (2010), p. 19 ↑

-

Sonia Ryang, ‘The Great Kanto Earthquake and the Massacre of Koreans in 1923: Notes on Japan’s Modern National Sovereignty,’ Anthropological Quarterly, 76.4 (2003), p. 738 ↑

-

Ryang, ‘The Great Kanto Earthquake and the Massacre of Koreans in 1923: Notes on Japan’s Modern National Sovereignty,’ p. 737 ↑

-

V.I. Lenin, ‘Introduction of Socialism or Exposure of Plunder of the State?’ (1917) <https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/jun/22.htm> ↑

-

V.I. Lenin, ‘The Collapse of the Second International’ (1915) <https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1915/csi/vi.htm> ↑

-

David A. C. Addicott, ‘The Rise and Fall of the Zaibatsu: Japan’s Industrial and Economic Modernization,’ Global Tides, 11.5 (2017), p. 2 <https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1259&context=globaltides> ↑

-

Addicott, p. 5 ↑

-

Addicott, p. 2 ↑

-

Addicott, p. 6 ↑

-

G.C. Allen, A Short Economic History of Modern Japan 1867-1937 (Routledge, 2003), p. 52 ↑

-

Kazuo Shibagaki, ‘The Early History of the Zaibatsu,’ The Developing Economies, 4.4 (1966), p. 545 ↑

-

Makoto Itoh, Value and Crisis: Essays on Marxian Economics in Japan (Monthly Review Press, 2020), p. 13 ↑

-

Kawashima, pp. 26-27 ↑

-

Kawashima, pp. 26-27 ↑

-

Kawashima, pp. 26-27 ↑

-

Kawashima, pp. 26-27 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 28 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 28 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 11 ↑

-

Kawashima, pp. 26-27 ↑

-

Kawashima, pp. 26-27; Yamada, p. 5 ↑

-

Karl Marx, Capital, Volume I (Penguin Random House, 1992), p. 781 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 28 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 32 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 38 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 34 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 34 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 34 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 34 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 34. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 37. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 38. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 38 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 38. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 39 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 39 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 41 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 44 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 44 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 44. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

Marx, Capital, Volume I, p. 929 ↑

-

Kawashima, pp. 41-43. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 130 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 145 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 156. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 35 ↑

-

Marx, Capital, Volume I, p. 557 ↑

-

Marx, Capital, Volume I, p. 557 ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ p. 105 ↑

-

Michael Weiner, ‘Koreans in the aftermath of the Kanto earthquake of 1923,’ Immigrants & Minorities: Historical Studies in Ethnicity, Migration and Diaspora, 2.1 (2010), p. 22. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

Weiner, p. 7. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 145 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 146 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 146 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 146 ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 146. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 146 ↑

-

Kawashima, pp. 70-71 ↑

-

Kawashima, pp. 70-71. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

Hasegawa, ‘The Massacre of Koreans in Yokohama in the Aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923,’ p. 116 ↑

-

Marx, Capital, Volume I, p. 254 ↑

-

Marx, Capital, Volume I, p. 342 ↑

-

Karl Marx, ‘Preface to the First German Edition of Capital, Vol. I’ (1867) <https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/p1.htm>. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

Marx, Capital, Volume I, p. 739 ↑

-

Ryang, ‘The Great Kanto Earthquake and the Massacre of Koreans in 1923: Notes on Japan’s Modern National Sovereignty,’ p. 737 ↑

-

Ryang, ‘The Great Kanto Earthquake and the Massacre of Koreans in 1923: Notes on Japan’s Modern National Sovereignty,’ p. 738. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

Kawashima, p. 84 ↑

-

Lie, p. 5. Emphasis mine. ↑

-

‘Family tragedy indicative of S. Korea’s remaining war wounds,’ Hankyoreh (2010) <https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_national/427055.html> ↑

-

Young Sik Kim, ‘The Left-Right Confrontation in Korea – Its Origin’, Association for Asia Research, 11, 2003 <https://web.archive.org/web/20080329203002/http://www.asianresearch.org/articles/1636.html> ↑

-

‘Waiting for the truth: A missed deadline contributes to a lost history,’ Hankyoreh (2007) <https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_national/218141.html> ↑

-

‘Dozens killed as Palestinians flee Israel’s new offensive on Khan Younis,’ Al Jazeera (2024) <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/7/22/dozens-killed-as-palestinians-flee-israels-new-offensive-on-khan-younis> ↑

-

Karl Marx, ‘Marx to Kugelmann in Hanover’ (1868) <https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1868/letters/68_07_11-abs.htm> ↑

-

Nikki Dejan Floyd, ‘Bridging the Colonial Divide: Japanese-Korean Solidarity in the International Proletarian Literature Movement,’ Yale University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses (2011), p. 274 ↑