by Rafael Lubner

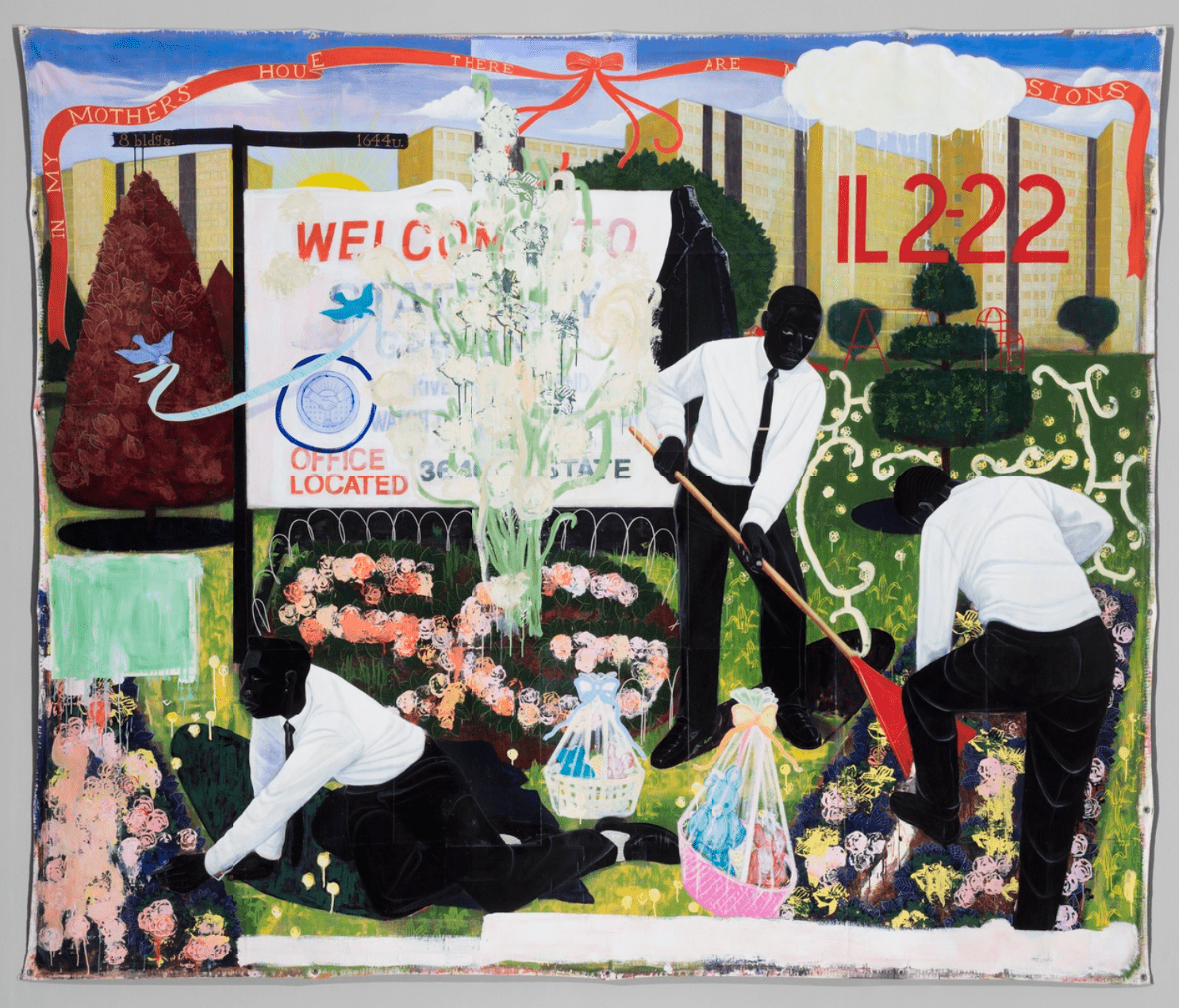

Header Photo: Kerry James Marshall ‘Many Mansions’ 1994

“The Association for The Advancement of Creative Musicians is an organization of staunch individuals, determined to further the art of being of service to themselves, their families and their communities… We are like the stranded particle, the isolated island of the whole, which refuses to expire in the midst of the normal confused plane which must exist—in order that we may, but with which we are constantly at war. We are trying to balance an unbalanced situation that is prevalent in this society.” – Maurice McIntyre’s manifesto from the first issue of the AACM’s newsletter, The New Regime.[1]

Whither autonomy?

On November 28th 1968, in the midst of Italy’s ‘hot autumn’, a group of student-workers occupied what had once been the Hotel Commercio, in Milan’s Piazza Fontana. A protest against the lack of accommodation in the city, the student-workers renamed it ‘Casa dello Studente’ (Student’s House), and then ‘Casa dello Studente e del Lavoratore’ (House of the Student and the Worker). Cooking, sleeping and working inside the building, and covering its exterior with signs and graffiti, these proletarians transformed the space into an extension of their ongoing struggle against capitalism’s domination of social life.[2] Until their eviction nine months later, they had, in their own words, “got their hands on the city.”[3]

Three years earlier, on May 8th 1965, at a kitchen table on East 75th street on Chicago’s South Side, a group of jazz musicians met to discuss the formation of what would come to be called the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM).[4] Conscious that the kind of music they played – which emphasized originality, creativity and experimentation – was at odds with the sorts of music dominant in Chicago at the time, and of the concomitant difficulties in making a living from its performance, these musicians created an organization with which they could present this music to the world. Over the next fifty years, the AACM would expand and change, producing multiple generations of players and recordings, reshaping the landscape of American experimental music in the process.

In their creation of structures which contest the vicissitudes of racial capitalist sociality, the students and the musicians draw our attention to particular aesthetic and social forms which breach the ongoing functioning of this system, forging apertures through which we can glimpse an autonomous world of experimentation, invention and collective flourishing. To think with the actions taken in Italy and Chicago is to be drawn to the potential inherent in artistic production and cultural transformation in the enactment of social worlds that depart from our own. In what follows, I take these moments of creation as the starting point for an exploration of the entangled scheme of collectivity, art-making, survival and resistance in order to approach an understanding of autonomy that takes seriously the figurative and analytic role played by culture in general, and music in particular, in carving out different forms of communal being from the bedrock of capitalist life. It is my contention that a collective, experimental understanding of culture and music provides us with a new grammar for thinking and enacting autonomous ways of living together and that contemporary political projects which seek the transformation of the social would be wise to look to the experiments of the Italian radicals, the AACM and those who follow in their wake.

Operaismo and Autonomia: Contexts and Strategies

First, Italy: the site of an immense revolutionary wave that consumed the country for a decade, and the rise of two theoretico-political tendencies that remain crucial for any understanding of the capacities and failures of autonomy – operaismo (workerism) and autonomia (autonomism). While a total reconstruction of the histories of these tendencies is beyond the scope of this essay, it is worth dwelling on some key aspects of the economic and social conditions from which operaismo and autonomia emerged, as well as outlining some of their signature theoretical contributions, in order to begin our tracing of the relation between autonomy, culture and politics.[5]

Italy in the 1950s was a country in the midst of a rapid economic and social transformation. The devastation of World War Two was giving way to an ‘economic miracle’ as aid from the Marshall Plan enabled the modernization of the country’s industrial base and introduced Fordism to the country’s factories.[6] This process of capital accumulation occurred against the background of a decade of persistent low wages and high unemployment among the working class, which significantly weakened their power at the same time as it intensified regional inequalities, with most of the new investment going to factories in the Northern cities of Genoa, Turin and Milan. As a consequence, workers in the South of the country were transformed into a reserve pool of labor who ensured that wages remained low for workers country-wide.[7] Sensing an opportunity to destroy the organizational and political gains made by workers in their resistance to Fascism during the war years, Italy’s business class and their allies in the political classes presided over a wave of mass firings, violent police repression of strikes, and the suppression of militant workers within factories.[8] Rather than pushing back against the aggression of the owners of capital, Italy’s main trade unions – the Italian General Confederation of Labor (CGIL), the Italian Confederation of Workers’ Trade Unions (CISL) and the Italian Labor Union (UIL) – pursued a reactive, defensive strategy, competing amongst themselves to be the workers’ representatives for the bosses, and fighting to preserve workers’ position within the existing hierarchies and structures of the Italian economy.[9] The combined force of capital’s expansion and the loss of power amongst workers laid the foundations for a massive expansion of productive activity between 1958 and 1963, which fundamentally upended Italian society – economically, culturally and politically.

Within this context, the old certainties of Italian Left politics, which since the end of the war had been dominated by the Italian Communist Party (PCI) and the Italian Socialist Party (PSI), began to wither away, and in its stead emerged a new series of propositions, theories and politics.[10] Rejecting a primary fidelity to the political party as the organizational form best suited to the advancement of working class interests, operaismo (workerism), as this tendency came to be known, sought to recenter the working class as the agents of their own liberation in the movement from capitalism to communism. A departure from the strictures of the ‘party’, whether in the guise of the PCI, the PSI or the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and from capitalist rationalization and sociality, the liberatory politics of operaismo was tied to an autonomy of and for the working class.

One of the exemplary figures of this shift towards an autonomous working class during this period was Raniero Panzieri, whose writing and political activities in the 1950s were influential in shaping the form of the activities and theorizations undertaken by militants, activists and theorists in the years leading up to the ‘hot autumn’. Panzieri, a member of the PSI’s Central Committee, sought to distance the Italian Left from the ambit of Stalinism on the one hand and social democracy on the other, and to instead focus on a reinvigoration of Left culture, based on “direct democracy, autonomous cultural institutions, and workers’ control.”[11] Culture, thought broadly, was therefore a practical concern for Panzieri, and its transformation had to be internal to the class struggle, accomplished through the production of knowledge about the working class, which they could use to understand themselves in relation to capital, free from the ideological mediations of the parliamentary Left, the unions or the factory owners.[12] To create this kind of autonomy, one that would reposition the working class at the heart of revolutionary struggle, required starting with the “conditions, structures and movement of the rank-and-file.”[13] Such sociological research, inspired by Marx’s notion of the workers’ inquiry,[14] was to be collective in nature, a ‘co-research’ responsive to the imbricated development of new working conditions and modes of consciousness amongst the workers, and which would, necessarily, result in transformations of the consciousness of those conducting the enquiries.[15] This collaborative knowledge-production would go hand-in-hand with the construction of autonomous workers’ institutions from which economic and political power could be built, which were not beholden to those external to the working class, whether in the form of the State, the party or ‘traditional’ intellectuals.[16]

With Panzieri, we have our first formulation of the relation between autonomy, politics and culture: autonomy is a structure that stands outside the current politico-economic arrangement, that is built in and through struggles for emancipation, by arrogating political, economic and social power to the group in question. Culture is of central concern in the production of this autonomy, existing as a system of shared understandings, knowledges and practices by which groups can achieve a necessary level of coherence to advance collective demands and produce new modes of resistance, survival and flourishing. There is a formal synchrony at play here in the development of radical politics and culture, with both being generated from within, rather than being imposed from without, a view which placed Panzieri in opposition to the dominant political culture within the left at the time, which was heavily wedded to the hegemony of the party apparatus––it was the party that was to operate as the guide for the workers’ movement and the trade unions.[17] This top-down approach had, according to Panzieri, resulted in the abandonment of the class struggle, as the PCI’s Stalinist politics reduced the working class to a tool in history’s teleological unfolding, while the leadership of the PSI sought success in electoral politics through social democracy and coalition building, leaving the working class behind.[18]

Panzieri’s proposal for the renovation of a left political culture through direct involvement with the workers’ movement was intended to cut through this stagnant, reactive political ecology. In and against the failure of the apparatuses and institutions which were meant to offer protection, support or guidance in the midst of the capitalist world, Panzieri proposed the creation of new systems, organizations and collectivities that would be responsive to the conditions on the ground, the practices of survival and resistance that form within the rhythms of laboring and living. To create such new structures from the wreckage of the old necessitated an attentiveness to tactics, form and genre, as well as an openness to contingency and pragmatism in order to ensure that new modes of subversion, resistance and militancy were not passed over, and to avoid the structures of the old being idly imported into those that comprise the new. Within Panzieri’s conception of politics and culture, we therefore see an orientation towards the immediate and the quotidian, a focus on what people are already doing and the tactics which are already being deployed in the service of survival. Autonomy, in other words, finds fertile ground in the terrain of the social.

At a theoretical level, this attentiveness to the social was reflected in the development of the ‘social factory’ thesis, a concept first developed by Mario Tronti in Quaderni Rossi.[19] Tronti traced the leakage of capital’s determination of social relations from its place in the factory to the social field more generally. “When”, as he puts it “specifically capitalist production has already weaved the whole web of social relations, it itself emerges as a generic social relation.”[20] The social becomes a space shaped by the logics and dictates of capital, resulting, dialectically, in the movement of the struggle into this same space – out of the factory and into the streets, the home and the university. Such a struggle is necessarily a general one, contesting the social factory at every point in which it is instantiated through a rejection of the logics underlying it, a strategy that came to be known as the ‘refusal of work’.[21] This ‘refusal of work’ was more than just the withdrawal of labor in the form of a strike, but the folding of the strike into a much broader rejection of productivity, the wage-relation and the commodity-form as the modes through which life was to be organized and contained. And at the height of the ‘hot autumn’, in the wave of wildcat strikes that rocked Fiat factories in 1969, these forms of refusal were sharpened into a series of contractual demands that “struck at the core of the capitalist organization of production in postwar Italy” both inside and outside the factory.[22]

The Flowering of Autonomia

It is at these Fiat factories – in particular the flagship Mirafiori factory – that we can move from operaismo to autonomia, as it is there that, following Balestrini and Moroni, the struggles which began in 1968 culminated, and a new cycle of struggle began.[23] On March 29th 1973, after weeks of struggle in protest at an inadequate agreement between the unions and the bosses, a new type of proletarian occupied the factory. Educated in the student struggles of the ‘hot autumn’, they produced a new understanding of autonomy, one which moved entirely beyond unions and parliamentary politics to strike at the edges of the capitalist system itself, creating another world to be inhabited. For these proletarians, autonomy meant that the workers’ very existence, a community of proletarian solidarity, could organize the social conditions of exchange, production and cohabitation independently from bourgeois legality. Autonomy from the law of exchange, from the law of selling one’s time, from the law of private property. The principle of autonomy assumed its full etymological meaning: proletarian sociality would define its own laws and practices under bourgeois military occupation.[24]

Here, the creation of autonomy moves from a posture of survival and resistance within the structures of the world as they are, to a generalized antagonism that unfolds into the production of a world that could be. In so doing, these proletarians reframe and extend Panzieri’s conception of autonomy, which despite its critique of contemporary Left political culture, and the role of the party in particular, was still very much wedded to it. By creating their own forms of living within the midst of the capitalist world, the occupants of Mirafiori began the process of moving beyond it, elevating the refusal of work to a totalizing ontological principle. At the same time, autonomy in this form renegotiated and clarified the relation between the individual and the collective, as unlike operaismo – which was concerned primarily with the advancement of workers’ power, and therefore brought with it a relatively coherent (and workerist) set of tactics, journals and organizations – autonomia operated as a combination of diffuse groups and movements, all held under the umbrella of the theory and practice of the ‘refusal of work’.[25] This expanded set of political goals, each with its own locations and tactics for struggle, bound together by a shared and total opposition to the capitalist world, birthed a mobile subjectivity that braided the individual into the collective, one the expression of the other. Nanni Balestrini captured these twinned poles in the breathless poetics of his Gli invisibili (The Unseen), written a decade later, an account whose form is shaped by the radical political invention of the period: unequivocal, experimental and multiplicitous. We might look, for example, at Balestrini’s description of an occupation’s aftermath:

at the same time the first working groups had been formed and had moved into the rooms on the first floor Valeriana and a group of women were meeting to set up a collectively run clinic others were planning a counterinformation service on soft and hard drugs others were discussing food and the counterculture others music film theatre there’s a decision to get in touch with the youth circles in other towns that we’ve heard from to exchange news and experiences and to set up a resource centre with their newspapers and their documents and in another room on the first floor a press office was already in full-time operation with typewriters and duplicators parcels of leaflets of press releases announcements documents were piling up on the tables of the press office waiting to go out[26]

It is this expanded understanding of autonomy that dominates Italian radical politics for the remainder of the 70s. And it is in the practices of the so-called ‘creative autonomia’, a collection of counter-cultural practices, communication networks, radio stations and publishing houses, that we can see the importance of culture within this milieu. Through their commitment to the proliferation of aesthetic forms, the participants in ‘creative autonomia’ sought to bring cultural practices into the realm of the political, folding one into the other until the separation between the two ceased to exist. They understood theirs was a historical conjuncture in which “the world of the imagination and its social production were the new grounds on which transformations were being carried out.”[27] The ‘Historic Compromise’ between the PCI and Christian Democracy (DC), which was proposed in 1973 and formalized in 1976, had re-established the central role of work to Italian society and resituated the working classes within capitalist hierarchies, through the “reeling in of wage levels, the containment of workers’ struggle and an intensification of security measures.”[28] This new program of austerity was not confined to the economy, but pervaded the cultural sphere, establishing “a deathly form of cultural conformism,”[29] which made clear that the terrain of culture was a battlefield from which the shape of a new world was to be wrought. For these autonomists, cultural production and creative expression were tools that could be used to reestablish the lineaments of a world that operaismo had shaken to its foundations and in the creation of new worlds that moved beyond the imaginative capacities and extractive rhythms of capitalism.

In the years leading up to 1977, this movement took the form of an explosion of publishing houses, magazines, journals and radio stations aligned to autonomia, with Balestrini and Moroni writing that “between winter 1976 and July 1977 […] 69 new series came out, with a total print run of 300,000 copies of which 288,000 were sold.”[30] Meanwhile, a decision by the Constitutional Court to liberalize the airwaves in June 1976 resulted in the expansion of free radio stations from major cities to provincial centers and towns.[31] The cultural production that emerged from this context privileged irony and nonsense, with autonomists cutting and pasting slogans into mass-produced newspapers, assembling to chant contradictory slogans and broadcasting strange new words and sounds over the radio.[32] These fractured aesthetics were pitched against the networks of an emergent digital capitalism that was seeking to map, quantify and valorize the totality of the activities that made up the social world, an effort that necessitated the circulation and control of information, the subsumption of intellectual labor into the circuits of value production and the proliferation of apparatuses of surveillance.[33] “The task ahead”, write the A/traverso collective in their book Alice è il diavolo, “is to subvert the information factory, to disrupt the information cycle, the collective organization of consciousness and of writing.”[34] A new collectivity was brought into being by this “swarm of experiments,” [35] one that was multifoliate and internally differentiated, pushing in all directions in its subversion, covering the quotidian with indeterminacy––an ever-unfolding flow of meanings. Participants in this aesthetic experimentation understood their semiotic actions to have concrete effects. Responding to an article on the new languages of the avant-garde written by Umberto Eco, Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi and Angelo Pasquini argued that “the socialization of style and the problematics of the literary avant-garde could not be reduced to a purely communicological fact, but needed to lead to a radical redefinition of productive relations, social identity and power.”[36] Here, culture and cultural production are not epiphenomenal to politics but entangled with it, simultaneously reordering the semantic, the imaginative and the material structures that comprise this world.[37] To create autonomous culture was to participate in this process of redefinition; by entering into these collectivities, pitching in with one’s skills, whether that involved establishing a small press to distribute magazines, drawing cartoons or reading poems on the radio, one was sharing in the construction of a new, different world.

And finally, a more youthful, countercultural valence of the movement brought the practice of autonomy to the consumption of culture, adding the expropriation of tickets to the cinema or rock concerts to the practices of espropri proletari (proletarian shopping) and autoriduzione (self-reduction) that were employed elsewhere.[38] The members of these ‘proletarian youth clubs’ (PYCs), refused the theft of everything that made life worth living by the capitalist system, choosing instead – as Balestrini describes above – to squat in buildings and put on plays and parties. As one group explained:

Our life is sucked out of us for 8-10 hours every day through exploitation. […] We’re forced to feel useless in a society that destroys social relations, human relations. How can we not want everything? How can we not want to be masters of ourselves, in the present and the future? For it to be us to choose how our bodies, minds and feelings are formed? […] We organized parties because we want to have fun together, we want the right to our lives, to happiness, to a new way of being together. We occupy buildings because we want to have places to meet, discuss, play music, put on plays, invent, to have a place that isn’t family life.[39]

By centering art and culture in the organization of their social worlds, these proletarians construct modes of living that foreground creation and joy, departing from the rhythms and social relations of laboring towards radically different conceptions of life and collectivity. Moving from the suburbs, these groups materialized these demands in the middle of the city, setting up the first ‘squatted/self-managed social centers’ (CSO/A), including the Centro Sociale Leoncavallo in Milan, which was established in 1975 and still exists to this day. Alongside the pursuit of new ways of feeling and being with one another, members of the PYCs looked to create structures that would enable these spaces to be of service to those living near them, and so, in the case of the Centro Sociale Leoncavallo, the occupiers, in concert with local residents, outlined a list of structures they saw as lacking from the neighborhood, and which could be built together. These included childcare and medical facilities, a library, and spaces for culture and discussion, a physical manifestation of the expanded autonomy first glimpsed in the occupation of Mirafiori.[40] In these occupations, we can discern the invention of another world, arranged on a radically different set of priorities and desires to the one that we currently inhabit. Enacting a general antagonism to the strictures of capitalist space and sociality, these proletarians propose a form of living that both reveals and contests the insufficiency of capitalism as a system for human flourishing. Autonomy: the invention of a new world in the desiccated soil of the old one.

The unfinished creativity of the AACM

And it is at the site of this new world coming into existence in the midst of the old that we can turn to the AACM. Founded in Chicago in 1965 by Muhal Richard Abrams, Jodie Christian, Steve McCall and Phil Cohran, the AACM emerges in the wake of the ‘Great Migration’, the mass movement of African Americans from the rural Southern states to the industrializing North, which began in 1916 and continued into the 1930s. Chicago was one of the primary destinations for this migratory wave,[41] with Southerners seeking an escape from the racist violence to which they were subject in the South and attracted by the promise of higher wages in the city’s factories.[42] Upon arrival in Chicago, migrants soon realized that the North was no promised land, finding themselves barred from higher-skilled (and therefore better paid) jobs and forced into overcrowded, decaying housing stock in the so-called ‘Black Belt’ of the city’s South Side. In spite of this marginalization, the South Side, and in particular a neighborhood called Bronzeville, became a hub for commerce, music and performance in the 1940s and 1950s, boasting several large theatres and a number of smaller clubs, which hosted the pre-eminent jazz musicians of the era.[43] Many of the first generation of AACM members cut their teeth in these spaces, watching and performing with contemporaries and elder statesmen alike. These experiences of movement, loss of both land and home, depravation and cultural efflorescence were crucial in shaping the first generation of the AACM’s understanding of artistic possibility, as well as making clear the nature of the U.S.’s racial and political hierarchies.[44] Bronzeville’s heyday was short-lived however, and by the beginning of the 1960s, the South Side was in the midst of economic decline and cultural retrenchment, with many of the key venues of the previous decades shutting down as part of a more general economic downturn taking place in black urban areas countrywide.[45] For players like Abrams, Christian, McCall and Cohran, interested in exploring the potentialities of improvisation and in the creation of ‘original music’, this dearth of spaces threatened both their creative and economic livelihoods. The AACM was therefore conceived as an organization that could ensure the survival of this music and the players who performed it: a safe harbor in an arid economic and cultural landscape.

From the very first meeting that led to the Association’s formation, it was clear that the creation of ‘original’ music would have to be a collective endeavor, requiring the fostering of a community of musicians to write and perform the music, and an audience that would engage with it, ensuring its survival within a hostile and indifferent world.[46] Reflecting on the AACM some forty years into its existence, Roscoe Mitchell frames the participatory nature of the AACM as follows, arguing that “the AACM is more than an organization. It is a lifestyle.”[47] This distinction is an instructive one, as it highlights the means through which the AACM’s survival was to be grasped and the location from which its form of autonomy was to be produced. It is an autonomy that comes into being in and through a refusal of the given shape of the social, which then necessarily stretches towards the creation of alternate forms of sociality. And in order to produce these forms, there was a need for an analysis of the cultural, economic and social systems in and against which it was to be posed – a workers’ inquiry of sorts – an effort taken up in the AACM’s initial meetings. Here, a discussion of the definition and nature of original music and the locations where it might be produced unfolds into a more general meditation on their position within the economic and cultural structures of the U.S. George Easton, a saxophonist, put it like this:

“‘Original,’ in one sense, means something you write in the particular system that we’re locked up with now in this society. We express ourselves in this system because it’s what we learned. As we learn more of other systems of music around the world, we’re getting closer to the music that our ancestors played and which we are denied the right to really stretch out in. […] We’re locked up in a system, and if you don’t express in the system that is known, you’re ostracized. And there are many, many, far too many good musicians put in that position because they don’t, uh . . .”

“Conform,” said a voice.

“But there are far better systems,” Easton declared. “As we tried to progress in jazz, we find that there’s expression on a much higher level than we had been led to believe. And presently, we will be locked up for the rest of our days in this system unless we can get out of it through some means such as this.”[48]

The limitations of what can be played, where and with whom are problems of both aesthetics and politics, and therefore require a hybridly aesthetico-political response: the building of new collective structures, which will in turn enable new forms of expression to emerge. For the AACM, the creation of original music is always enmeshed with the creation of collectivity. Indeed, Easton is arguing here that the development of higher forms of musical expression, which would not be limited by the aesthetic, political and economic structures of the U.S. in the 1960s, cannot be implemented without collectivity at the level of organization and artistic expression. To go beyond the given requires the formulation of a mode of social and aesthetic being that seeks out freedom in what can be made common and shared. And as in Italy in the 60s and 70s, such collective social and aesthetic forms are tied to the creation of a possible future, taking on an prefigurative dimension in its movement beyond the entrenched structures of U.S. racial capitalism. Here, the hope for a better future borne by their parents as they travelled North is transmuted into organizational and aesthetic forms that likewise seek a different world.

Alongside these discussions of collectivity, a related set of discussions takes place in the AACM’s initial meetings concerning the autonomy of the individual within this collective structure. They begin with some members arguing for a movement beyond a simple notion of personal freedom towards something more closely resembling ‘self-determination’.[49] As Muhal Richard Abrams puts it:

“All music is good, and I’m sure that this group will not be a source of cutting anyone off from doing most of the things that they want to do, but at least we would have something that would definitely and directly push us at all times, personally, because this is what we need. We need to be remembered as representing ourselves.”[50]

Muhal Richard Abrams

Here we see a calibration of the contradictions inherent to personal autonomy in light of the need for collective expression, underwritten by the assumption that within the confines of the AACM, one’s personal freedom is inherently bound up in the fortunes of the collective. By existing within the Association’s bounds, individual members will be pushed to create music that represents themselves, a framing that hides a slippage into the communal, as each member’s individual creativity also acts to generate artistic forms associated with the AACM as a whole. The balancing of the individual within the communal is, as George Lewis notes, characteristic of African American music both before and after jazz, but with the AACM, we see this relation operating at the aesthetic and social levels simultaneously: both within the compositions produced by the Association and in the organizational structures to which it holds.[51] To create original music, the individual must be mediated by the collective, the latter providing the former with a frame through which an aesthetic can be articulated. Or as Abrams and Mitchell put it:

“You can’t say, ‘Where did the AACM music come from?’” Muhal’s tone was forceful. “The AACM is a collection of individuals!”

“You have the original, and then you have this constant desire to recreate the original,” Roscoe observed. “Now, somewhere that gets really watered down. The AACM was more aimed at creating an individual than an assembly line.”

“But we have something in common!” Muhal was excited now. “For example, we are in agreement that we should further develop our music.”[52]

In this movement between the individual and the common, we can observe a crucial aspect of the AACM’s construction of autonomy: both the music produced within the AACM and the social form that frames it are defined by experimentation, the bringing in of new elements and the reworking of foundational assumptions in the service of its ongoing development; theirs is an open, unfinished and unfinishable structure.[53] There is a necessary connection between this kind of movement of and for experimental music and an approach to the political that likewise moves through an experimental mode––experimental in the sense of improvisation, the emphasis of process over end. We see this in the flowering of revolutionary energy in Italy, which manifests in multiple formations, tendencies and tactics, and it is central to the AACM’s survival.

And this experimental, unbounded form of autonomy is, crucially, a function of the AACM’s blackness, necessitating a shift in our epistemological and auditory frames if we are to apprehend its implications for our account of autonomy.[54] To think with black music as it relates to autonomy is to enter into a space of instability and movement. Within such a space, one must be attentive to breaks and kinks, to the moments in which the communal is summoned in and against a world that undermines both the possibility of this communality and the individuals who find shelter within it. Listening for autonomy in what, with Fumi Okiji, we would call the sociomusicality of the AACM requires looking for “the stranded particle, the isolated island of the whole, which refuses to expire in the midst of the normal confused plane which must exist—in order that we may, but with which we are constantly at war.”[55] Such a requirement refocuses our attention towards the incomplete, the partial and the as-yet-unrealized. Both at the level of the aesthetic and the social, the kind of autonomy proposed by the AACM is one that is always on the move, a function of the need to survive in a hostile world, of the twinned necessity for creation and originality. Wadada Leo Smith explains that the foundational nature of community to the AACM is one “based around not just existence but an ongoing revolution, new ideas, a new way of thinking and an idea that is based on the actuality that once you come up with a beautiful idea, you have to put it into effect.” Through collectivity, originality, revolution and practice the community is brought into the world and comes to survive within it, “[a]nd, from that, the community grows and expands, you know, and the idea of that, which is really great and benefits to the whole community in every way, also expands.”[56] This approach goes some way to explain the AACM’s fifty year lifespan: it remains engaged with its surroundings, continuing to show its merits to those outside of it. A practice of autonomy that speaks only to those already convinced is limited; a better world has to be built so that others will inhabit it. Bearing the AACM’s unfinished nature in mind we might then crystalize our argument as to the relation between experimental music and socio-political forms. Following Okiji, who asks whether it might be the case that jazz “makes a virtue of irresolution and incompletion,”[57] I would argue that the AACM offers us an aesthetics and a sociality that is always in the business of creating unresolved structures into which others can enter. This irresolution and incompletion allows “space in the same story for many others,”[58] creating a ground from which others might continue to create original musical and social forms. It cannot be known what new shapes will be taken by this new music, what new sounds it might look towards, or what social organization might undergird it, all that can be known is that the material that forms its foundation will be constantly reworked, restated and retried. This is the politics proposed by the AACM, the transposition of communal improvisation, the movement of the jam from the rehearsal space into daily life, until the separation between the two ceases to matter. Autonomy here is the creation of a space into which others can be welcomed, where they too might be inspired to pick up an instrument and play.

Playing with the AACM: Moor Mother and Angel Bat Dawid

One way that we might observe the effects of this understanding of politics and culture in practice is to look to two current inheritors of the AACM’s sociomusicality: Angel Bat Dawid and Moor Mother. Both are entangled with the Association in a number of ways, and represent a continuation of its experimental approach both aesthetically and politically.[59] Take Moor Mother’s performance with Nicole Mitchell – a member of the AACM since the 90s – Offering. Across three improvised pieces, we witness a ceaseless movement through a foreboding landscape, a long walk through a desolate terrain, limned by electronic sound that is itself in the process of constant change. Both musicians torque and twist texture and tone, bells giving way to brittle noise, a flute staggering through the murk. The sound is spacious, enfolding the listener gradually, Moor Mother’s words providing phrases that coil in on themselves, sibilants nestled amidst drawn out exhalations of frustration. This is an open and contingent music, one that bristles with the potential to exist otherwise elsewhere. We can contrast these wide sonic vistas with the tightly wrapped sound Moor Mother produces alongside the group Irreversible Entanglements.[60] Here, a different kind of movement is embraced, one that is violent and forceful, tracking the coerced migration of Black people across the United States with a sound that probes and demands, bass and drum tracing circuitous groove, saxophone and trumpet curling together like smoke.

Such attentiveness to movement and mutability is present across Moor Mother’s oeuvre, both at the sonic level and in her interest in collaboration. Moor Mother moves across genres, interlacing her poetics – a tangle of anger, terror, repetition and accusation – and finding collectivity in her embrace of and by a wide swathe of explorers: rappers, pioneers of free jazz, experimenters in contemporary electronics.[61] With her music, our focus is drawn to the importance of the unfinished and the ongoing provided by the AACM’s framework for autonomy; Moor Mother’s is a project whose development requires experimentation, creativity and originality, a tactile collaborative posture which allows her to embed herself within the sounds of others, a seeking out of space that is at the same time a seeking out of kin. Like the sociomusicality of the AACM, Moor Mother inhabits a protean zone of continual reinvention, remaining in friction with the changing world, finding new sounds and new collaborators with which she might continue the unfinished work of survival.

From Angel Bat Dawid we can draw a different but related conclusion. Like Moor Mother, Dawid’s musical practice is wide-ranging and capacious; founded primarily in jazz but incorporating a wide range of tones, sounds and genres. On this year’s Hush Harbor Mixtape Vol. 1: Doxology, percussion and echo demarcate space, underwritten by clarinet, and watched over by synth and voice. That voice is multiplied, autotuned and pitched up, providing an aperture through which the interweaving of the singular and the multiple can enter: Dawid performing as both individual singer and chorus. As these elements are slowly drawn together, we come to focus on the lyrics, which orbit themes of gratitude, rest and home, elaborating on the titular ‘hush harbor’, a space born in the violence of the antebellum South, “where Black folks could speak frankly in Black spaces in front of Black audiences.”[62] These “informal, unofficial meeting places such as cane breaks, woods, praise houses, funeral parlors, juke joints [and] the Chitlin’ Circuit […] were necessary to the maintenance, circulation, and affirmation of African American knowledge,” allowing those within them to hold religious services and learn to read and write.[63] The hush harbor is a space that can only function outside of the general social field, enacted in a vestibular, provisional zone, and Dawid’s invocation of it calls attention to the subversive nature of black survival, the requirement to maintain secrecy and community amidst hyper-surveillance.[64] Hush here is a sonic form that calls for quietness, that gestures towards a retreat, an opening up of space into which others might join and dwell.

By appending the secretive nature of this space to Moor Mother’s unyielding search for sound and kin, we might find a location to conclude our meditation on autonomy. If with autonomia we witnessed an eruption into the social, a foregrounding of culture in political struggle, with the AACM and its descendants, we find autonomy’s fugitive obverse, an opaque, unfolding creation of music and space, one whose survival is entwined with its ceaseless looking forward, its refusal to stay settled. It is a mode of living that cannot but be communal, even as it falls out of view, retreating into spaces that must remain in obscurity. And it is then a form of aesthetico-political expression that invites contribution and reflection, even as it remains mobile and mutable, unable to be fully fixed––you have to know where to look and how to play in order to enter. “There is”, Okiji writes, “much to be explored concerning that incomprehensibility, about how such life, inaugurated in obscurity, comes into view in its invisibility, clothed in images and imaginings of a hostile society.”[65] An autonomy created after autonomia and the AACM, after Moor Mother and Angel Bat Dawid is an autonomy whose refusal of the given is sounded through a music that repels and enfolds, that takes nothing for granted, that binds fear to joy, that creates a collectivity whose creativity and mutability is its strength. Through this improvisation, we begin to bring a different world into being.

***

Rafael Lubner is a writer and academic based in London.

Notes

- See George E. Lewis, A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), p. 190. Emphasis added. ↑

- This brief account of the Hotel Commercio’s occupation draws from Nanni Balestrini and Primo Moroni, The Golden Horde: Revolutionary Italy, 1960-1977, trans. by Richard Braude (Calcutta, India: Seagull Books, 2021); David Palazzo, The “Social Factory” In Postwar Italian Radical Thought From Operaismo To Autonomia (City University of New York, 2014) <https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/262>; and Giulio D’Errico, Squatted Social Centres in England and Italy in the Last Decades of the Twentieth Century (Aberystwyth University, 2019). <https://pure.aber.ac.uk/portal/files/31144433/DErrico_Giulio.PDF>. ↑

- Balestrini and Moroni, p. 275. Footage of the occupation can be found at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OFRoj5R-dIo ↑

- Here, and elsewhere when discussing the AACM, I am drawing primarily from George E. Lewis, A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009). ↑

- Steve Wright, Storming Heaven: Class Composition and Struggle in Italian Autonomist Marxism, 2nd Revised edition (London: Pluto Press, 2017) is generally considered the authoritative rendering of this history for an English language audience, but as above, I have also found useful David Palazzo, ‘The “Social Factory” In Postwar Italian Radical Thought From Operaismo To Autonomia’ (City University of New York, 2014) https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/262; Patrick Gun Cuninghame, ‘Autonomia: A Movement Of Refusal: Social Movements And Social Conflict In Italy In The 1970’s’ (Middlesex University, 2002), as well as the recently translated Nanni Balestrini and Primo Moroni, The Golden Horde: Revolutionary Italy, 1960-1977, trans. by Richard Braude (Calcutta, India: Seagull Books, 2021). ↑

- As Wright explains, in the immediate aftermath of the war, “Industrial production stood at only one-quarter the output of 1938, the transport sector lay in tatters and agriculture languished. A combination of inadequate diet and low income (real wages had fallen to one-fifth the 1913 level) meant that for large sectors of the population, physical survival overrode all other considerations.” These conditions were especially visible in the north of the country. See Wright, p. 5. ↑

- See Palazzo, p. 50. ↑

- See Palazzo, pp. 50-52. ↑

- See Palazzo, p. 54. ↑

- As Palazzo explains, the stranglehold of the PCI and the PSI on left culture in the post-war period brought with it a focus on “electoral politics, class alliances, a renewal of the South as necessary to completing bourgeois democracy, an intellectual apparatus subservient to the party’s strategic needs, and unconditional support for the Soviet Union in the Cold War.” Palazzo, p. 59. ↑

- Palazzo, p. 64. ↑

- Specifically, “by studying the working class as a separate category of analysis, Panzieri argued that workers’ inquiry could shed light on working class subjectivity and capture an understanding of the “concrete form” in which the contradiction between capital and class was present.” Palazzo, p. 91. ↑

- Raniero Panzieri, La crisi del movimento operaio: Scritti interventi lettere, 1956–60 (Milan: Lampugnani Nigri, 1973), p. 254. Quoted in Wright, p. 19. ↑

- See ‘Karl Marx: A Workers’ Inquiry (1880)’ <https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/ni/vol04/no12/marx.htm>. ↑

- As Fabrizio Fasulo puts it, “The object of the inquiry is at the same time the subject of the investigation, a subject involved in a simultaneous process of gaining awareness and therefore involved in a change occurring at the centre of the cognitive dynamic.” Fabrizio Fasulo, ‘Raniero Panzieri and Workers’ Inquiry: The Perspective of Living Labour, the Function of Science and the Relationship between Class and Capital’, Epherema: Theory and Politics in Organization, 14.3, 315–33 (p. 323). ↑

- As opposed to the Gramscian ‘organic’ intellectuals involved in class struggle. ↑

- The latter, as Palazzo has it “were largely ‘transmission belts’ for party politics.” Palazzo, p. 67. ↑

- Panzieri was particularly critical of the decisions taken by the leadership of the PCI in response to the events of the 1956, which saw them recommit to a model of international communism with a country’s national party at its helm, denounce the workers’ uprising in Poland and support the Soviet Union’s suppression of the Hungarian Revolution. See Palazzo, pp. 67-68. ↑

- A journal founded by Panzieri in 1961 that was crucial in the development of Italian radical thought and practice over the next two decades. See Palazzo, p. 83. For the English translation of Tronti’s essay, see ‘Factory and Society’ in Mario Tronti, Workers and Capital (London: Verso Books, 2019), pp. 12-35. ↑

- Tronti, p. 24. Emphasis in original. ↑

- “Indeed” Tronti explains, “by this point it is no longer simply possible but historically necessary to root the general struggle against the social system within the social relation of production; in other words, to pitch bourgeois society into crisis from within capitalist production.” Tronti, p. 30. ↑

- Palazzo, p. 318. These demands included “a reduction of the work week to 40 hours for all categories, movement towards normative parity between operai (blue-collar workers) and impiegati (white-collar workers), equalization of salary for those under twenty years old, and the right of assembly and meetings in the factory.” Palazzo, pp. 317-318, quoting Vittorio Foa, Sindacati e lotte operaie (1943-1973), Documenti della storia (Torino: Loescher, 1975), p. 185. ↑

- See Balestrini and Moroni, p. 443. ↑

- Balestrini and Moroni, pp. 445-446. ↑

- These included anti-fascist, feminist and environmentalist groups, among others. As Patrick Cuninghame puts it, each group “protect[ed] and advance[ed] their own agendas without being subsumed by the demands of a wider collectivity, whether civil society, the working class or other social movements.” Patrick Cuninghame, ‘Autonomia in the 1970s: The Refusal of Work, the Party and Power’, Cultural Studies Review, 11.2 (2005), 77–94 (p. 79); For a more in-depth account of autonomia’s composition, see Patrick Gun Cuninghame, ‘Autonomia: A Movement Of Refusal: Social Movements And Social Conflict In Italy In The 1970’s’ (Middlesex University, 2002). This next section draws primarily on Cuninghame’s research, both in his PhD thesis and his subsequent articles. ↑

- Nanni Balestrini, The Unseen, trans. by Liz Heron (London: Verso, 2012), p. 48. ↑

- Balestrini and Moroni, p. 611. It is worth noting that the establishment of communication and imagination as grounds for transformation goes hand-in-hand with the development of new mass media and communications technologies occurring contemporaneously. ↑

- Balestrini and Moroni, p. 618. ↑

- Balestrini and Moroni, p. 618. ↑

- Balestrini and Moroni, p. 595. ↑

- See Cuninghame, p. 183. ↑

- Cuninghame explains that “The free radio stations, most famously Bologna’s Radio Alice (as in ‘Alice in Wonderland’), and to a lesser extent in the more ‘political’ Radio Sherwood in Padua and Radio Onda Rossa in Rome, became the sites not just of a localised dissemination of counter-information and subversive ideas, through the cronisti a gettone (telephone kiosk reporters) and phone-ins, but also the locus for continual linguistic experimentation through the use of ‘transversalism’, ‘maodadaism’, ‘nonsense’ and a mixture of false and real news (‘Let’s spread false news that produces real events’).” Cuninghame, p. 183. ↑

- For a genealogy of this mode of capitalism that both builds on and critiques the theories developed within Italy during this period, see Tiqqun, The Cybernetic Hypothesis, trans. by Robert Hurley, Intervention Series (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Semiotext(e), 2020). ↑

- Collective A/traverso, Alice è il diavolo (Franco Berardi and Ermanno Guarneri eds) (Milan: ShaKe, 2000 [1976]), quoted in Balestrini and Moroni, p. 609. ↑

- Balestrini and Moroni, p. 607. ↑

- Balestrini and Moroni, p. 610. ↑

- However, as Balestrini and Moroni point out, there is a certain historical irony to this holding together of culture and productive relations when viewed in light of the latter subsumption of the kind of creative and cultural work performed within this strand of autonomia under the schema of ‘immaterial labor’. Nevertheless, as I will argue in more detail later in this essay, there is still much to be drawn from a movement that threads culture through politics as part of its revolutionary charge. See Balestrini and Moroni, p. 607. For one of the more influential theorizations of immaterial labor, see Maurizio Lazzarato, “Immaterial Labor” in Paolo Virno and Michael Hardt (eds.), Radical Thought in Italy: A Potential Politics, (University of Minnesota Press: 1996), pp. 142–157. ↑

- Paying a reduced amount for goods, or stealing them. See Cuninghame, p. 175. ↑

- See Balestrini and Moroni, p. 522. ↑

- See Cuninghame, pp. 177-178. ↑

- As James R. Grossman writes, “from 1916 to 1919, between fifty and seventy thousand black southerners relocated to Chicago”, and its black population grew from 44,103 in 1910 to 109,458 in 1920. James R. Grossman, Land of Hope: Chicago, Black Southerners, and the Great Migration (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), p. 4. ↑

- This included physical abuse, lynching and forced displacement from their land, a practice known as ‘whitecapping’. See Grossman, p. 17. ↑

- This area, which was known as ‘Black Metropolis’, was also the location for a number of important community institutions, including the Provident Hospital, the George Cleveland Hall Library, the YWCA, the Hotel Grand, the Parkway Community House and the Boulevard Garden Apartments. See St Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton, Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City, Enlarged edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015) for a much-cited contemporary account. ↑

- “The migrants’ twin assertions of mobility and agency,” Lewis argues, “set the stage for how these musicians looked at artistic practice later in their lives.” Lewis, p. xxxvi. ↑

- Roscoe Mitchell argues that in the South Side’s case, a new raft of licensing laws that discouraged performances by larger groups were to blame for the closure of venues. Whatever the specific causes, the consequences were stark – George Lewis quotes cultural historian and saxophonist Leslie Rout, who affirms that by 1967, “there did not exist on the South Side of Chicago a single club that booked nationally established jazz talent on a consistent basis.” See Lewis, p. 86 and Leslie B. Rout, Jr., “Reflections on the Evolution of Post-War Jazz,” Negro Digest, February 1969, 96. Quoted in Lewis, p. 85. ↑

- Members of the organization were expected to pay dues, perform original compositions with other members, and as the Association developed, participate in the education of younger musicians. An exemplary instance of this joining of originality and communality is the AACM Big Band, an ensemble comprised of the Association’s membership which performed every Saturday. As Leroy Jenkins explained to Val Wilmer, “the rules were that if you wanted the band to play your music, you had to write for everybody – I don’t care if they were playing the kazoo.” Val Wilmer, As Serious As Your Life: Black Music and the Free Jazz Revolution, 1957–1977 (London: Serpent’s Tail, 2018), p. 154. ↑

- Douglas Ewart, Nicole Mitchell, Roscoe Mitchell, Famoudou Don Moye, Matana Roberts, Jaribu Shahid, Wadada Leo Smith, and Corey Wilkes, ‘Ancient to the Future: Celebrating Forty Years of the AACM’ in People Get Ready: The Future of Jazz Is Now!, ed. by Ajay Heble and Rob Wallace (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), pp. 244-264, p. 247. ↑

- Lewis, p. 102. ↑

- See James Boggs, ‘Black Power: A Scientific Concept Whose Time Has Come’ in Racism and the Class Struggle: Further Pages from a Black Worker’s Notebook (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1970), pp. 51-62 for a contemporary articulation of this concept. ↑

- Lewis, p. 101. ↑

- See Lewis, p. xii. ↑

- Ekkehard Jost, Jazzmusiker: Materialen zur Soziologie der afro-amerikanischen Musik, (Frankfurt am Main: Ullstein Materialen, 1982), p. 184. Quoted in Lewis, p. 498. ↑

- George Lewis puts forward the argument that “perhaps at least part of [the AACM’s] dynamism was derived from the clarity with which its members realized that the project could not really be completed; its unfinished nature became its crucial strength.” Lewis pp. xxvii-xxviii. ↑

- Here I am thinking of blackness as that which issues from but is not reducible to the existence and experience of African Americans in the U.S., naming something that both underwrites the social and extends far beyond its current construction. Or as Fred Moten puts it, “what if blackness is the name that has been given to the social field and social life of an illicit alternative capacity to desire?” Fred Moten, ‘Blackness and Nothingness (Mysticism in the Flesh)’, South Atlantic Quarterly, 112.4 (2013), 737–80 (p. 778). ↑

- See Lewis, p. 190. Okiji writes that “Black music is sociomusical play. It is not so much that it represents black life or an alternative human future; rather, it demonstrates to us how to acquit ourselves toward blackness (and toward another world). It shows us how we might go about dispositioning ourselves, so that we might know how it feels to be a conflicted subject—both human and inhuman, American and black (African), and both “the black” and heterogeneous, fecund blackness.” Fumi Okiji, Jazz as Critique: Adorno and Black Expression Revisited (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2018), p. 4. ↑

- ‘Ancient to the Future: Celebrating Forty Years of the AACM’ in People Get Ready: The Future of Jazz Is Now!, ed. by Ajay Heble and Rob Wallace (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), pp. 244-264, pp. 247-248. ↑

- Okiji, p. 68. ↑

- Okiji, p. 68. ↑

- Moor Mother participated in We Are On The Edge, a celebration of the Art Ensemble of Chicago’s 50th anniversary, and Angel Bat Dawid has often spoken about the importance of the AACM to her development as a musician. See https://artensembleofchicago.bandcamp.com/album/we-are-on-the-edge-a-50th-anniversary-celebration and https://toneglow.substack.com/p/038-angel-bat-dawid. ↑

- See Irreversible Entanglements (2017), Who Sent You? (2020) and Open The Gates (2021). ↑

- George Lewis argues that AACM gesture towards a kind of experimentalism that moves through boundaries and genres, finding commonality in multiplicity – a formulation drawn from Hardt and Negri, making clear the link to autonomia – laying the foundations for a new kind of musician who moves across genres “with fluidity, grace, discernment, and trenchancy.” See Lewis, p. 510. ↑

- Vorris L. Nunley, Keepin’ It Hushed: The Barbershop and African American Hush Harbor Rhetoric (Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press, 2011), p. 23. ↑

- See Nunley, pp. 23-24. ↑

- For an alternate approach to surviving in public while black, see Angel Bat Dawid & Tha Brotherhood, Live, which begins with a denunciation of the racism experienced by Dawid and her band while on tour in Western Europe and moves through rage and defiance in its exploration of the music from her album The Oracle. ↑

- Okiji, pp. 82-83. ↑