Imagining Expanse: Crisis, Surplus, and Liberatory Futures in “You Ought to be Ashamed/Expanse” by Cécile McLorin Salvant

You'll be sorry, you just wait and see

Just you wait and see

Wouldn't treat a dog the way you treatin' me

way you’re treatin' me

Chloe Murr

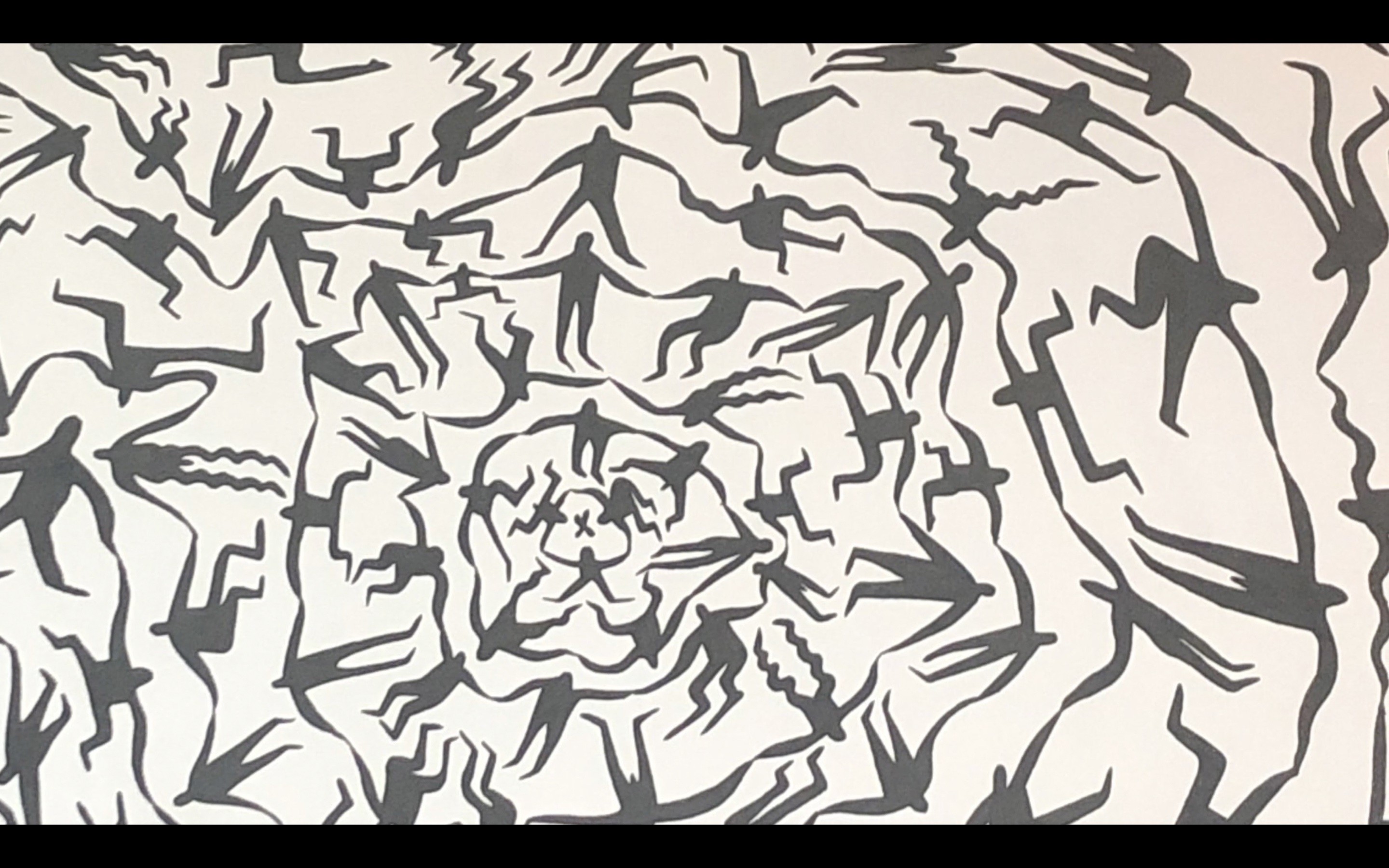

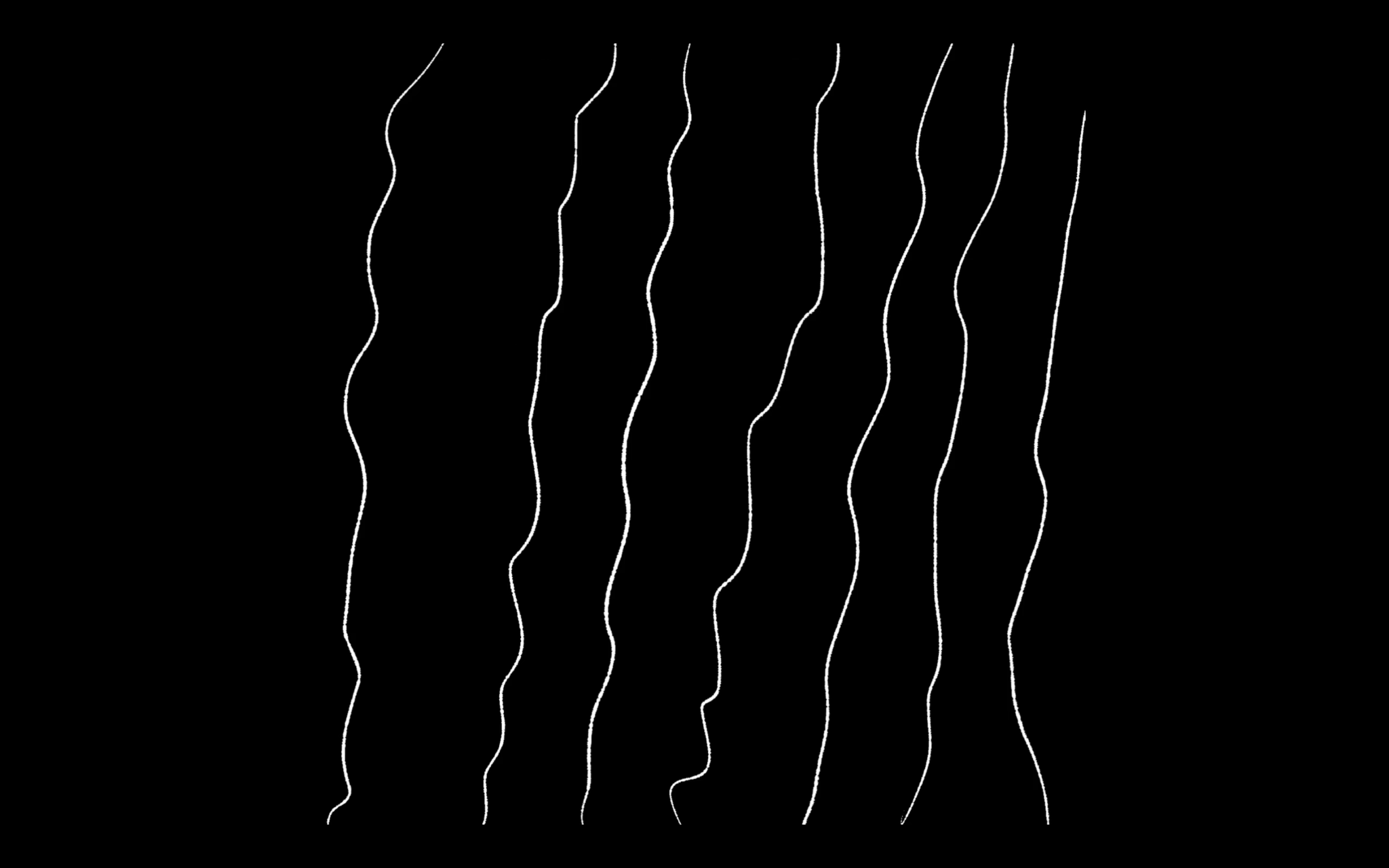

The sonorous voice of the singer and visual artist Cécile McLorin Salvant mourns a future landscape in social, political, and economic crisis. Just you wait and see. As white line drawings flash against a black void, contracting, stretching, and erupting into abstracted clouds, Salvant’s voice prophesies destruction, neglect, and (social)death, a future shaped by the prison industrial complex. “You Ought to be Ashamed/Expanse,” a music video created and performed by Salvant, audiovisually considers freedom as a place, presenting the vastness of imaginary space as cultivating the conditions of possibility for abolitionist futures. The anguished cover of a blues song, with original music and lyrics by Porter Grainger, juxtaposed with Salvant’s own song, illustrates the creative and cross-disciplinary practice that abolitionist and scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore argues is necessary to identify and promote multiple routes out of crisis.[1]

Over the last thirty years, in response to the nation's (over)reliance on its carceral system, the movement for prison abolition has gained momentum in the United States. The aesthetic practice of abolition –“a political vision with the goal of eliminating imprisonment, policing, and surveillance and creating lasting alternatives to punishment and imprisonment”– is situated between a critique of current social realities and imaginations of new ones.[2] The carceral system's impact pervades politics, economics, and culture, but its magnitude and power may not always be visible. One function of the prison abolition movement is raising public awareness of this reality, exposing the prison’s influences and its social effects. By visualizing this power, the movement is able to proceed towards action that addresses the system as it currently stands. Prisons are often able to operate outside of public perception because they exert and are imbued with visual power that reinforces and naturalizes their place within social landscapes, controlling what (and who) is visible to the public. While prison populations are subjected to surveillance and compulsory visibility by guards, the buildings themselves are often hidden in plain sight, disguised as warehouses or simply located in rural areas. The visual power that connects seeing, knowing, and authority constitutes a visual reality for politics and social relations that impacts how the world is seen and might be contested or remade. As a result, this power can be critiqued through the visual, so from the East to the West Coast: posters, pamphlets, artworks, and exhibitions present abolitionist discourse in and through visual culture. This turn to the visual gives the abolition movement access to institutions and audiences that would not otherwise contend with prisons as an issue that affects them. Through the public presentation of this visual analysis, the influence of prisons and carceral institutions is not limited to those who are incarcerated.

“You Ought to be Ashamed/Expanse” is Salvant’s audiovisual offering to the burgeoning field of artists contributing and committed to the radical vision of a world without prisons. Featured in “Music for Abolition,” a program of original music videos directed by three-time Grammy award-winning drummer, producer, and educator, Terri Lyne Carrington, Salvant’s video premiered alongside the songs of musicians including Lisa Fischer, Nicholas Payton, and Carrington’s band Social Science.[3] As part of Visualizing Abolition, a public scholarship initiative at the University of California Santa Cruz, developed by Gina Dent and Dr Rachel Nelson, “Music of Abolition” attempts to create a soundtrack for a political movement with an abolitionist vision. In response to the visual power embedded in prisons and the carceral system which operates spatially and politically, Visualizing Abolition uses public exhibitions and educational curricula to propose alternative ways of seeing. By including music in their documentation of multidisciplinary aesthetic approaches to the struggle for prison abolition, the program extends modes of seeing carceral structures and resisting their power into new sensory dimensions.

PLAUSIBLE FUTURE(S)/ JUST YOU WAIT AND SEE

The State of California is often highlighted by Gilmore, Angela Y. Davis and others as a “plausible future for politics,” as the State’s vast resources have allowed it to act, build, and legislate in ways that others cannot.[4] From the 1970s to the early 2000s, California’s economy grew exponentially, with currency in circulation expanding tenfold from 50 billion to 500 billion dollars.[5] As the State prioritized capital's needs, it also completed the construction of twenty-two new prisons. This period of growth fundamentally restructured California’s relationship with its population, shaping an unfolding crisis culminating in its current 2.3 million prison population.[6] As the United State’s largest economy, California became a representation of a future landscape built on “prison foundations” and carceral infrastructure that other States seek to reproduce.[7]

Gilmore argues that such an expansion of carceral infrastructure “must be situated in the political-economic geography of globalization.”[8] Through the 1970s and 80s in California, there commenced a surplussing of “finance capital, land, labor, and State capacity,” which exploited existing racial, economic, and political issues and contributed to carceral expansion. The surplus appeared as newly mobilized finance capital alongside an excess of investable cash with limited outlets, as well as economic and environmental crises forcing agricultural land out of production. Consequently, the State was faced with a growing surplus labor force –greatly impacted by deindustrialization, displacement, and mechanization– and a limited capacity to absorb it into social programs and infrastructure.[9] Despite its recent economic growth, the State responded to the crisis with organized state abandonment –dismantling the welfare state and increasing the population of the economically vulnerable– and using its financial resources to create carceral infrastructure for these surpluses to be invested into.

Poet and scholar Jackie Wang emphasizes that moving many of the State’s socioeconomic responsibilities to the free market reframed the government’s primary social engagement as the provision of security.[10] The growing surplus population, a result of a merging social crisis and capital disorder, presented a problem that the State was only prepared to fix with the diagnosis of individualized lawlessness and universal carceral solutions.[11] The California government's newly transformed social function became the strategic maintenance of social life, managing and disciplining populations who had been expelled from the labor markets and were not covered by the State's limited resources.

Consequently, California began to enact laws in an attempt to maintain social order that guaranteed incarceration as a response to an increasing number of crimes while removing this population, and the social crisis they represent, from sight and public consciousness.[12] These apparatuses of power –from increased policing in urban areas to the Three Strikes and other Habitual offender laws– were spatialized and racialized, normalizing the mobilization of physical and political force by the State onto its constituents.[13] Gilmore explains that while African American men bore the initial brunt of this combined abandonment and attack, those with low incomes and unstable employment–determined by race, gender, class, and location–were also increasingly represented outside of the market and inside California’s prisons.[14] To Gilmore, prison expansion was the State’s “geographical solution to [its] socioeconomic problems,” the incarceration, en masse, of those Davis identifies as the “detritus of contemporary capitalism”.[15]

VISIBLE MUSIC AND MATERIALITY

To Fred Moten, the visual “is given its fullest potential by the aural,” so seeing clearly–and imagining the future–is facilitated by the spatiality and sensoriality of sound.[16] With In the Break, Moten explores the ways black performance, sound, and music articulates a shared political consciousness and pursuit of liberation that is unique to black radicalism. David Lloyd summarizes this as a theory of freedom in which the subject establishes “the conditions of possibility for any modern concept of the political.”[17] Fueled by a collective visualization of living beyond the exploitation and crisis of capitalist systems, the imaginative and resounding expressions of black music manifests “the future in the degraded present.”[18] Moten situates this knowledge of the future, first, in enslaved laborers, who produced speech and sound–expressing an inherent value that Marx’s description of commodities denies them. Moten critiques Marx to articulate his own theory of freedom and value as “something Marx could only subjunctively imagine: the commodity who speaks,” that is, the object’s ability to resist–both enslavement and other forms of subjugation–and “the performative essence of blackness” and black performance.[19]

Beginning with the “historical reality of commodities who spoke,” Moten argues that “Marx is unable to fully think the articulation of slave and commodity,” as something capable of speech.[20] As Marx believes that commodities are unable to speak, he constructs a voice for them, “magically given through the mouths of classical economists.”[21] Moten outlines this imposed voice as saying “our use value…does not belong to us as objects. What does belong to us, however, is our [exchange]value,” hence, “the commodity discovers herself, comes to know herself only as a function of having been exchanged.”[22] To Moten, Marx “places this discovery [of exchange-value] in an unachievable future,” disregarding the conditions of possibility that would garner such a discovery, and underestimating “the commodity’s powers, for instance, the power to speak and to break speech.”[23] Moten instead concludes that “the object’s (exchange)value is the fact–the material, graphic, phonic substance–of the object’s speech.”[24]

For Moten, the commodity that speaks establishes an “animative materiality–the aesthetic, political, sexual, and racial force–of the ensemble of objects that we might call black performances, black history, blackness,” and the conditions of possibility for resistance and freedom that they (re)produce.[25] The combination of forces into the “world-encompassing gaze” of black music and performance forms an ontology of “resistance to power and objection to subjection.”[26] Attention to sound in this instance creates an opening to “the sensual ensemble–of what is looked at,” and by extension, what can be imagined.[27] The materiality of black performance, therefore, manifests a “socialization of the surplus,” and the collective visualization of a social system completely transformed, a sight made clearer through sound, recording, and music.[28] Together, Moten and Gilmore form a theory of the surplus that extends the “material heritage” of enslaved laborers, commodities who spoke, to include those who are currently incarcerated, the animated force of which is expressed through “Music for Abolition.”[29] While art exhibitions form a significant part of Visualizing Abolition, just as Moten uses music to expand the visual, the addition of sound and music to the program contributes to its spatial and sensory breadth. In its wide-ranging critiques of the history of racism, oppression, and prisons in the U.S., “Music for Abolition” participates in the (re)production of the radical materiality that Moten says animates the “freedom drive” of black performance, and directs it towards the movement for abolition.[30]

“You Ought to be Ashamed/Expanse” emerges from the program as containing multiple, contrasting futures within the piece: one closely related to the present political landscape, and the other a boundless, imaginary space. Through the audiovisual piece, Salvant uses the production of sound to participate in the aesthetic practice of visualizing decarceral futures.

YOU OUGHT TO BE ASHAMED

You ought to be ashamed, ashamеd, ashamed

Ashamed of what you've done to me

But I will be the same, yes, the same

You can bet that I will always be

“You Ought to be Ashamed/Expanse” moves in that Black Radical Tradition, whereby tragedy and hope, pain and pleasure, are woven through lyric and performance to manifest liberatory futures.[31] Created and performed during the coronavirus lockdowns of 2020, in the wake of the summer’s antiracist uprisings, Salvant’s appropriation of “You Ought to be Ashamed” explores a bleak projection of the future that is bound to an experience and understanding of the present moment in crisis. Salvant’s voice cuts through the video’s hand-drawn illustrations, resounding with forceful disappointment while asserting an air of authority. You can bet that I will always be. Salvant’s vocals affirm her materiality and speech in opposition to the racialized injustice of present politics and the criminal legal system in the U.S.

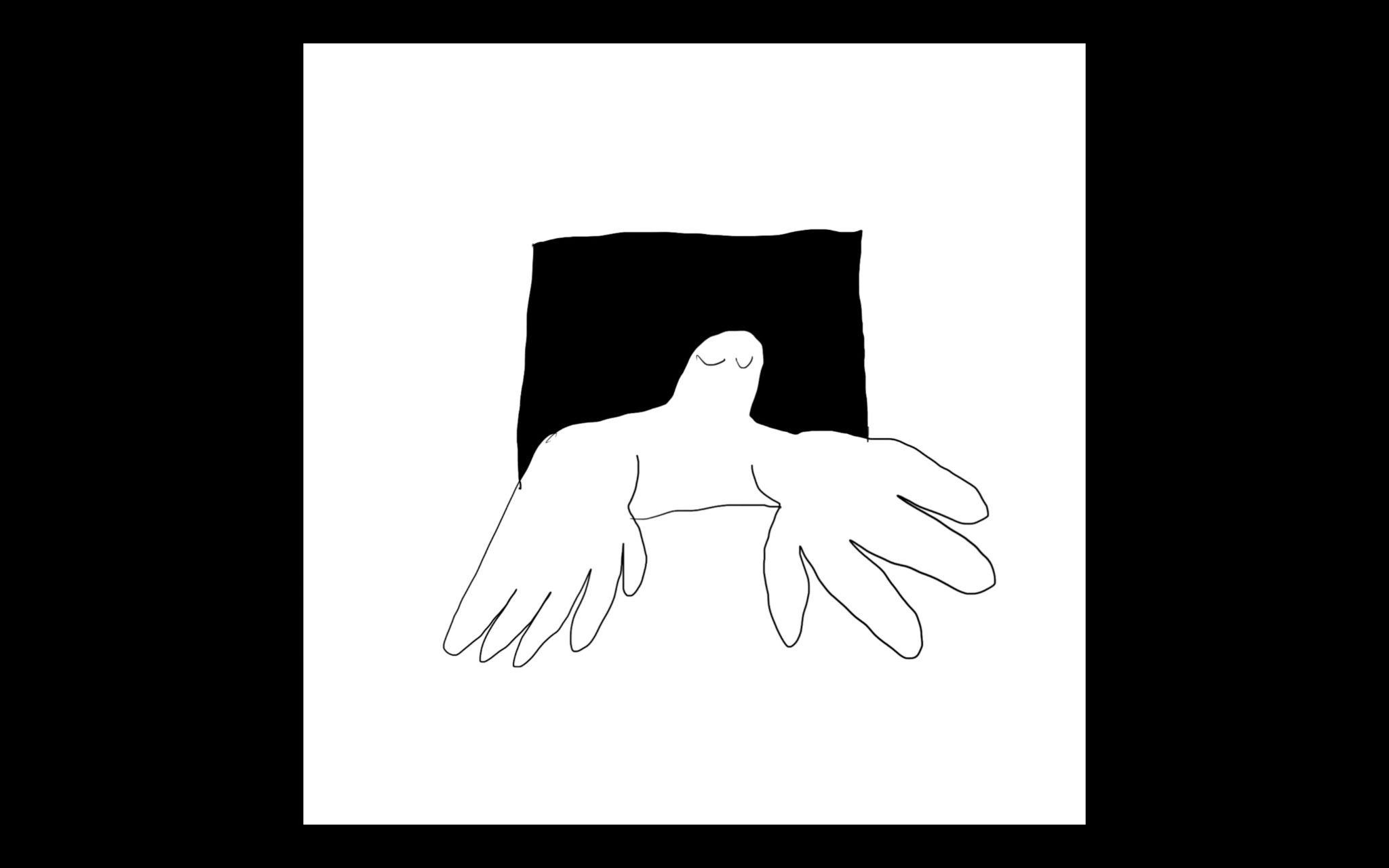

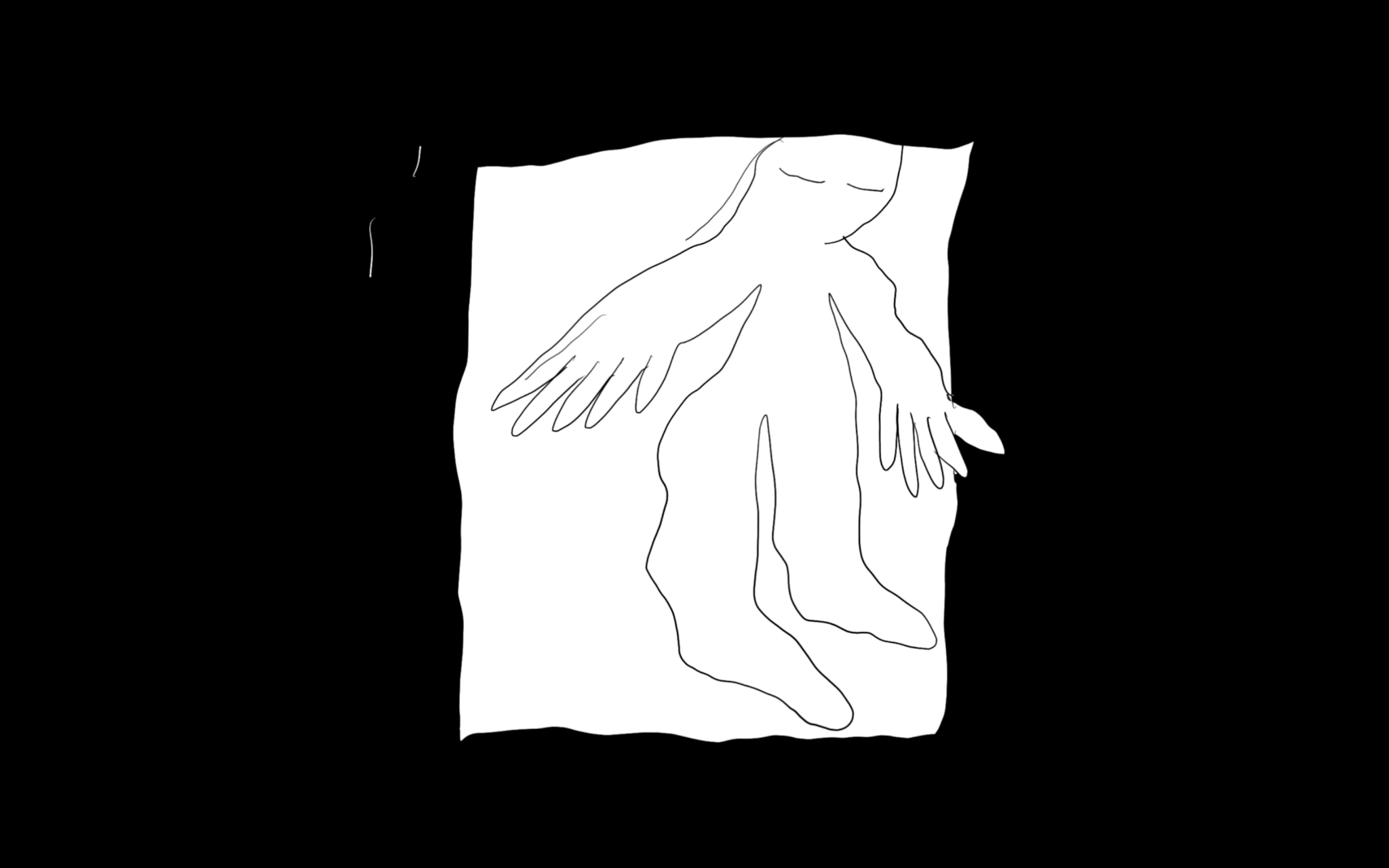

In the song's intense and sorrowful first half, Salvant’s words and drawings flash across the screen as a dark stream of consciousness. Then, contained by a black square, a white hill morphs into the head and shoulders of a human-like figure. The crescent lines of closed eyes emerge upon its face before colossal hands reach out of the black box, pulling the character from its enclosure and into the foreground. The warped body expands, losing its humanistic proportions to become a distressed amalgamation of gigantic hands and bulbous eyes. In this piece of visible music, Salvant’s performance represents the prison without reproducing the tropes of mass media–chains, bars, struggle, and death–that reinscribes harm while normalizing the existence of punishment and prisons as the sole remedy to social disorder.

Through the Visualizing Abolition program, Dent and Nelson emphasize the ways that artists and musicians, like Salvant, help cultivate ways of seeing, offering a creative and liberatory framework with which to critique prisons and other oppressive systems. The combination of sound and image offers a compelling medium to trouble the social preconceptions and power of the carceral system, which is often communicated through visual culture. Just as Moten identifies Marx's imposed voice and assumed understanding of the commodity that speaks, Dent points out that the reproduction of prison imagery in mass media–from The Wire to Brooklyn 99–leads people to assume they already understand it. Music is thus a productive force in the abolitionist movement, necessary to the aesthetic critique, which, as noted by Gilmore “[opens] on the ground, through which creative possibility can move.”[32] Instead of definitive conclusions or assumptions of meaning and speech, to Moten, music that moves in the black radical tradition is an “abundant refusal of closure,” and “an ongoing and reconstructive improvisation of ensemble.”[33] Moten, therefore, emphasizes that an “immersive lingering” in that refusal or opening is a “necessary preface to action,” a quality that is abundantly present in Salvant’s performance. Through the temporality of her lyrics, in “You ought to be ashamed” and “You can bet that I will always be” the intention to act is clear, but it is in the juxtaposition of the two songs and in lingering in the opening, which for Salvant, is “expanse,” that radical action becomes possible.

The work of artists, including Salvant’s music video, introduces a new and different vision of prisons and their abolition for the public.[34] Salvant’s black square could be a prison or an allusion to the present, however, its abstraction prioritizes emotion instead of representation. Therefore, beyond a simple refusal of prisons, her music video traverses their representations to complicate the public perception of prisons and their ideological social function. She plays with her drawn figure’s freedom of movement, at times capturing it inside rudimentary boxes while also allowing it to roam. In moving through the sonic as well as the visual, Salvant reproduces a radical political consciousness on an encompassing sensory level. When paired with the affliction in her voice and lyrics, Salvant’s recurring motif, its jolting animation and constant movement balances pain and oppression with pleasure, resistance, and conditions of possibility for liberation.

DREAMING OF EXPANSE

Some of us have been dreaming of

Expanse

Some of us have been slowly making plans

Expanse

A place where we can stretch our toes

Expanse

The kind of vastness where a body doesn’t know

Which way to go

In an interview about the series, Salvant admitted that in its first iteration, the piece was a standalone cover of “You Ought to be Ashamed”, directed towards the United States. The present political turmoil, an unraveling pandemic, economic instability, and environmental catastrophe form a crisis defined by plurality. Carrington prompted Salvant to “imagine the future too”, which was initially a challenge to Salvant.[35] In the same interview, Salvant admitted to feeling anxiety and pessimism clouding her vision of the future, however, she ultimately responded to Carrington’s suggestion with the addition of Expanse.

In comparison to the somber and monochromatic visuals of “You Ought to be Ashamed”, “Expanse” is a burst of color, a dreamlike configuration of abstract landscapes, pulsing clouds, and the reappearance of Salvant’s animated character wandering open fields on horseback. In “Expanse”, the soft chords of a piano accompany Salvant’s voice, which is equally mellow. The lyrics speak of a vastness and excess of space which animates the body and mind. True to her disclosure of pessimism, Salvant’s vision and performance of an alternative future also contain ominous elements. In one instance, a dynamic landscape is punctuated by a photograph of a mushroom cloud. In another the clouds are coloured red like the sunset before a storm, alluding to the distorted present that looms large in the first section. Her minor chords and concluding remarks on lacking comprehension of “which way to go,” juxtaposes the fatigue and endurance of revolutionary movements with the hopeful anticipation of attainable social change. While the admission of not knowing which way to go speaks to a collective anxiety about the stability of the future, the statement is still open to the possibility of something otherwise. Salvant’s video, therefore, proposes an ambivalent vision of the future imbued with a self-awareness of the fallibility of society. Nevertheless, there is liberatory potential in simply dreaming from within these conditions.

Beyond visualizing a physical location, Salvant’s imagination of a future without prisons is about dreaming and the conditions for living in the present that this generates. Some of us have been dreaming of/Expanse/Some of us have been slowly making plans. “Expanse” engages dreaming as a revolutionary act. In Freedom Dreams, Robin D. G. Kelley describes the way black revolt shaped the evolution of surrealism, as well as how surrealism recognized and confirmed a political self-consciousness that was already present in the black radical tradition.[36] For both movements, a revolution of the mind–dreaming–was essential for the reconstruction of social relationships and futures unbound by present conditions.[37] The poetics of music and performance are Salvant’s means for engaging with a political vision and abolitionist future from the current social realities of racism in the U.S. and the carceral systems which uphold it. Ultimately, Salvant’s map is not a step-by-step guide to a preconfigured future but insists on a surplus of space to dream of worlds that will serve and free the most people. “You Ought to be Ashamed/Expanse” is a revolutionary act, an invitation for others to unleash their “creative capacities” to imagine expansive liberation and collaboration, developing multiple routes out of crisis.[38]

SLOWLY MAKING PLANS

The spatiotemporal organization of “You Ought to be Ashamed/Expanse” forms a sense of a place that exists outside of the current social, political, and economic landscape imposed by prisons and other carceral institutions.[39] This musical contribution to the prison abolition movement emulates an “irruption of sound” which Moten stresses is necessary to add to Frederic Jameson’s theory of cognitive mapping, “[allowing] for both a description of post-modern global space and a prescriptive vision of that space transformed, resocialized.”[40] To Moten, sound “makes an understanding of that ensemble possible precisely by way of disruptive augmentation of the very idea of the visual picture” that Jameson relies so heavily on.[41] In moving beyond the visual–as Salvant does by sounding an imagined surplus of space–the tangible sensations of music extend mapping practices from prevailing systems of global space to the level of the (social) body and collective consciousness. Sound reconfigures the aesthetic, substituting the visual with aural modes of performing, “inhabiting and improvizing social/global space,” for a more comprehensive map that restructures the present towards the pursuit of social liberation.[42]

Currently, “You Ought to be Ashamed/Expanse,” like many of the other songs in the series, exists only as a part of the “Music for Abolition” program on the Visualizing Abolition website. However, there are live performances of the songs scheduled to take place at UC Santa Cruz in the near future. When the songs in the series were written and produced in 2020, they fulfilled an urgent need for new mediums for activism. Now they are being developed into a sustained abolitionist music program with both a local and potentially international reach. In this way, “Music for Abolition” addresses the present crisis–the instability of accumulation and dispossession, the overgrown carceral system–with the collective vision of prison abolition, encouraging both the continual dreaming of multiple futures, liberatory places, and mapping routes towards them.

Gilmore affirms that engaging creative practices with the space of the “external world” necessarily provides the conditions of possibility for changing it.[43] Likewise, Salvant’s song participates in an act of sonic visualization, reconfiguring aesthetic practice by dreaming through sound in a way that is sensuous and spatial, one that Moten maintains launches the commitment to action.[44] In connecting Salvant’s perspective of the present with a futural abolitionist vision, “You Ought to be Ashamed/Expanse” identifies a throughline from historical racial oppression to the current social landscape. This relation suggests that actions to prevent and reduce the harm enacted by the carceral system today must be viewed in connection with structural critiques and dreams of transformative futures.[45]

In a musical practice that is embodied and therefore “always spatial,” “You Ought to be Ashamed/Expanse” occupies physical and imaginary space as part of a place making practice.[46] And if freedom is a place, as Gilmore asks, how can such a place be (re)produced continually?[47] Salvant’s performance of a radical political consciousness manifests conditions of possibility and resistance that are not static, but ongoing and expanding, in multiplicity, through time. Her audio-visionary project forms a soundscape for both the current social system and an embodied, encompassing map of a world without prisons. In dreaming, Salvant imagines the place that is freedom and through her performance, she calls for the reproduction of that place, for abolitionist geographies, for generative space, for expanse.

Watch You Ought to be Ashamed/Expanse here, along with the entire Music for Abolition series

-

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Abolition Geography (Verso, 2022), 41. ↑

-

Angela Y. Davis et al., Abolition. Feminism. Now. (Hamish Hamilton, 2022), 51. ↑

-

“Visualizing Abolition - Music for Abolition,” accessed March 4, 2023, https://visualizingabolition.ucsc.edu/exhibitions/music-for-abolition.html. ↑

-

“Currency in Circulation,” March 30, 2023, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CURRCIR. ↑

-

Jackie Wang, Carceral Capitalism (Semiotext(e), 2018), 82. ↑

-

Gilmore, 8; Stanford Law School, “The “Three Strikes and You’re Out” law imposed a life sentence for almost any crime, no matter how minor if the defendant had two prior convictions for crimes defined as serious or violent by the California Penal Code.” See “Three Strikes Basics,” Stanford Law School, accessed March 10, 2023, https://law.stanford.edu/three-strikes-project/three-strikes-basics/. ↑

-

Gilmore, 203; Angela Y. Davis, Are Prisons Obsolete? (New York: Seven Stories, 2003), 17. ↑

-

Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 172. ↑

-

David Lloyd, “The Social Life of Black Things: Fred Moten’s Consent Not to Be a Single Being,” Radical Philosophy, no. 207 (2020): 079–092, https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/article/the-social-life-of-black-things. ↑

-

Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition, 8. ↑

-

Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition, 85. ↑

-

“Visualizing Abolition - Visualizing Abolition,” accessed March 4, 2023, https://visualizingabolition.ucsc.edu/exhibitions/visualizing-abolition.html#oct20. ↑

-

Robin D. G. Kelley, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination (Beacon Press, 2002), 187. ↑

-

Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition, 218. ↑